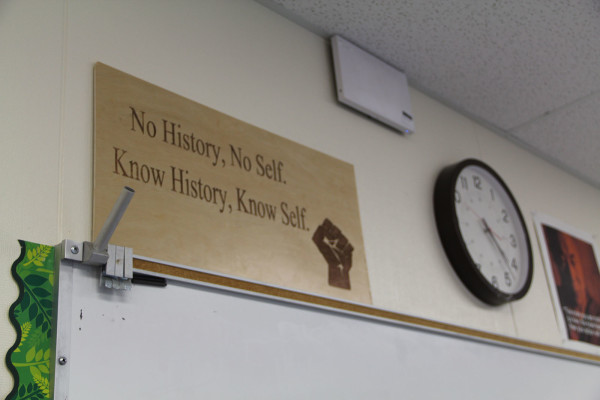

“No History, No Self. Know History, Know

Self.”

This is the sign that appears on Leona Kwan's ethnic studies classroom in Oakland Unified School District's (OUSD). It could be a slogan for the ethnic studies movement that has gained momentum across the United States, most especially Texas and California. Although it has been inspired by the struggle over Mexican American Studies in Tucson Unified, it is a deeper, decades-long struggle that finds expression in the presence of Mexican American Studies programs and departments in universities nationwide.

To wit, many of us in Texas are organizing through our National Association for Chicana and Chicano Studies (NACCS) Tejas Foco statewide organization that hosts an annual conference taking place this February18-20, Lone Star College-Kingwood with a focus on the preservation of "traditions, oral history, customs, dichos, folklore, language, food, religion, literature, music, education, folk art, Chicana/o history and how they affect our everyday lives and identity." Simultaneously, February 17-20 the Texas Association for Chicano in Higher Education (TACHE) annual conference is also taking place with a similar focus: ¡Adelante! Latinos on the Rise: Remembering our Past, Leading our Future. A recent statewide conversation on merging the bilingual education and Mexican American Studies agenda spearheaded by Texas State University professor Dr. Christopher Milk also took place in El Paso, Texas, at the Texas Association for Bilingual Education's annual meeting.

NACCS Tejas Foco has become a very large, well-attended conference in Texas due in no small part to the excitement of teaching Mexican American Studies at all levels of the educational system in Texas. While we still have to fight for inclusion at the State Board of Education level, as well as in textbooks, generally, our community doesn't have to wait for our officials to do the right thing in the meantime. And this is what is happening in California, too.

While it is regrettable that on October 9, 2015, Governor Jerry Brown vetoed a bill (authored by Assemblyman Luis Alejo) calling for ethnic studies statewide in California despite its support by state senate and house Democrats, school districts are nevertheless taking a lead. In OUSD—as in San Francisco, LAUSD, Pico Rivera, and most University of California campuses—the policy only requires its teaching of it at the high school level, but encourages it at elementary and middle school levels.

This is a great piece on so many levels. It speaks to the value of ethnic studies, generally, and specifically, to Oakland Unified School District's (OUSD) take on it: Not anyone can teach it; and it's as much about the content as it is about the authentic caring relationships between teachers and students. This approach helps children to feel both powerful and seen.

Angela Valenzuela

c/s

Ethnic studies courses to be offered at all OUSD high schools

“In terms of social studies content, there is no content that is more directly relevant to students’ lives or more academically rigorous,” said Leona Kwon, an ethnic studies teacher at Castlemont. “There might be these words that are really big, like ‘institutional oppression,’ but once you explain the concept, students can understand that right away because it reflects so much of their lived experience.”

Thanks to an Oakland Unified School District (OUSD) school board vote Wednesday night, within the next three years ethnic studies classes, like this one, will be offered at all Oakland high schools. The course may count as an academic graduation credit, and though the policy does not specify the course will be a graduation requirement, the possibility has been discussed by the board in previous meetings.

According to the district’s new policy, presented to the board by Young Whan Choi, civic engagement coordinator for OUSD, ethnic studies courses create “higher overall academic achievement, boosts in social emotional learning, increases in self-efficacy, higher graduation rates, and a reduction in drop-out rates.” The policy encourages elementary and middle schools to incorporate an ethnic studies curriculum, but will only require district high schools to offer the course.

The course, a general survey that will cover the histories of many groups of people, will be piloted by a small group of teachers during the 2016-2017 school year. A group of teachers is currently updating the framework for ethnic studies that will be used by teachers to develop the curriculum for their schools.

Recently, both local and statewide initiatives pushing schools to offer ethnic studies courses gained ground. This fall, San Francisco public schools began to offer ethnic studies classes in all high schools. However, on October 9, Governor Jerry Brown vetoed a bill, authored by Assemblyman Luis Alejo (D-Salinas) and supported by state senate and house Democrats, calling for the creation of a statewide ethnic studies curriculum.

For the OUSD, specific details about the proposed curriculum are not set in stone. At Castlemont, one of the few schools in the district that now offers an ethnic studies course, all 9th grade students take the class taught by Kwon, which she has taught for five years. Throughout the year, she focuses on concepts like personal identity and systems of privilege, which helps students think about how the different parts of their identities can effect their personal experiences and understand those experiences within a historical context. The course also focuses on the idea of race as a social construct—or that individuals who share a particular racial identity can be very physically diverse—and discussion of levels of oppression within society.

After taking the ethnic studies course, students “are able to place themselves within a historical context” said Kwon. “Through ethnic studies, they have such a better, more critical understanding of how society functions, both currently and historically, that is also very, very empowering.”

Michelle Flores, a 10th grade student at Castlemont, believes that her experience last year in Kwon’s classroom was key to her growth as a student and an individual. “Most people don’t know the real history. They know the dominant narrative,” said Flores. “It made me want to prove the stereotypes wrong. It made me want to give back to my community and teach my community about all the oppression that we’re going through, especially institutional oppression.”

“It just opened my eyes to the world,” said Taejin Kim, another 10th grade student at Castlemont.

“And now every time we see a Disney movie, it’s like ‘Whoa, they just said something racist there!’” said Flores.

Students from other OUSD high schools have also called for ethnic studies courses. At the October 14 school board meeting, student director Darius Aikens expressed his interest. “It gives students the ability to feel powerful,” said Aikens. “I don’t have ethnic studies at Oakland High, but I would like to have ethnic studies at Oakland High.”

One of the challenges the board has faced as it considered including ethnic studies in the curriculum at all Oakland high schools is finding the right teachers for the course. At the October 14 meeting, staffing was a main concern cited by board members. Director Hinton-Hodge (District 3) recalled the beginnings of the African American Male Achievement Initiative in 2010, a program dedicated to addressing the needs of African American students by offering an after-school mentoring program focusing on African history and culture. According to Hodge, before the program was introduced, African American students did not feel like they were being acknowledged or being given equal access to opportunities in the general education classrooms.

“Young people, young black boys, didn’t feel as though they were seen. They didn’t feel like people valued them, they didn’t feel as though that they could really learn,” Hodge said.

Hodge, who also said she was excited about the possibility of developing a system-wide ethnic studies curriculum, said she wants staffing to be carefully considered. “I don’t want to be pessimistic by any means, but I don’t want to see an investment in a curriculum when people don’t authentically care … with their heart and really love each one of our children who walk in there.”

“Not just anybody’s going to be able to teach this,” said Director Torres (District 5). “So we don’t want anybody saying, ‘Well I need a job and there’s this opening so I want to do this work.”

Kwon’s students say she is fully invested in creating a welcoming space for her students. “She’s really passionate about her job—that’s what makes her so amazing,” said Flores. Both Flores and Kim mentioned times when they missed class and immediately received a text from Kwon asking if they were OK.

Compassion like Kwon’s students see in her might benefit any classroom culture, but for an ethnic studies class, where issues like privilege and oppression are frequently discussed, sensitivity is key, Kwon says, and it is important that her classroom remains a safe space. “So much of ethnic studies is not just the content you teach, but how you teach it,” said Kwon. “It comes down to your relationships and sort of the culture you set up in your classroom.”

Awesome!! Thank you.

ReplyDelete