Also featured is LULAC President Domingo Garcia who I learned from watching the film on PBS last week is a descendant of those who experienced this vicious brutality at the hands of both the Texas Rangers and U.S. Military. I had the honor of working with Representative Garcia and his office in the Texas State Legislature when he was a representative back in the early 2000s. I always knew that there was something powerful that drove him, that impelled him forward as a powerful and impassioned civil and human rights advocate.

For me, one of the most important takeaways was the involvement of the U.S. military. I am so glad that this finally came to light. Yes, just like what's happening today along the U.S.-Mexico border, our ancestors' tax dollars paid for this heinous crime against humanity!

The documentary shows this Tuesday night at the Paramount Theater in Austin, Texas. Emilio and others will be providing commentary.

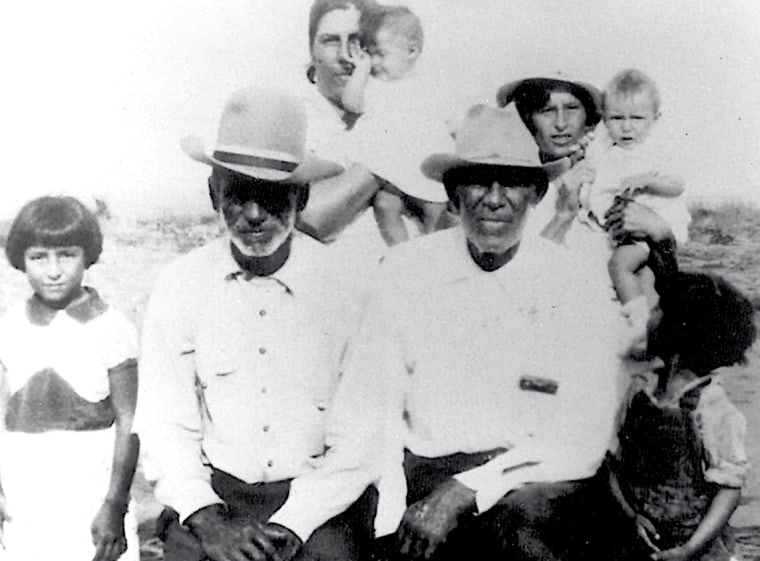

Last year, Texas Tejanos commemorated this event, as well, as you can see here:

Descendants gather at Capitol to mark 100th anniversary of Porvenir Massacre

This documentary helps explain the racist policies, politics, and violence that continue today along the U.S.-Mexican border which, of course, directly impacts those attempting to cross it for legal, justifiable reasons from other parts of Central and South America suffering from violence, crises, and economic and political instability.

It's moving to view images of the descendants who come together a hundred years later. What will the descendants today's victims have to say a hundred or fewer years from now in what is yet another terribly sad, violent chapter of U.S. history that we are currently witnessing before our very eyes?

I shudder the thought.

-Angela Valenzuela

'Porvenir, Texas' details massacre of Mexican Americans by U.S. soldiers, rangers

“People say the past is the past, and you’ve got to move on. Unfortunately, that is just not the case. Violence against Latinos ... has become more relevant."

By Raul A. Reyes

Arlinda Valencia was at a family funeral when she heard what sounded like a wild rumor. One of her uncles mentioned that the Texas Rangers had murdered her great-grandfather. This idea seemed so ludicrous that some of Valencia’s relatives laughed. No one believed the story. But the tale stuck with Valencia, and later she went online to read about Texas history.

At her computer, Valencia, who lives in El Paso, discovered an account of a massacre carried out by Texas Rangers. Among a list of the victims, she recognized her great-grandfather’s name. “His name was there,” she recalled. “The story was true. It sent chills down my back.”

Valencia’s great-grandfather Longino Flores had indeed lived in the small West Texas border town of Porvenir. In the early morning hours of Jan. 28, 1918, a group of ranchers, Texas Rangers, and U.S. Army cavalry soldiers entered the village and rousted the residents from their beds. They led away 15 unarmed men and boys of Mexican descent to a nearby bluff, where they shot and killed them. These victims ranged in age from 16 to 72, and some were American citizens. The town’s women and children fled across the border to Mexico for safety. The next day, the perpetrators returned and burned the village to the ground. Porvenir ceased to exist.

This dark episode in Texas history is the subject of a documentary, “Porvenir, Texas,” directed by the late Andrew Shapter. The film is streaming until Oct. 19 on PBS.org. It will have a free premiere screening in Austin, Texas, on Oct. 1, followed by an El Paso screening on Oct. 4.

Christina Fernandez Shaper, a producer of the film, believes that the story of Porvenir needed to be told. “I am Mexican American myself, I am from Texas, my family has been here for generations. And I know we all have stories in our families, sometimes of land being taken from us or other injustices.”

The story of Porvenir might have been lost to history if not for two men. One was Harry Warren, who taught school in the village and wrote an account of seeing the bodies of the dead. The second was José Tomás (“J.T.”) Canales, a state legislator who in 1919 launched an investigation into the Rangers. Although he lost his case, the depositions and testimony he obtained have provided historians with a trove of information.

That investigation also led to a major reform of the Rangers, helping make them into the organization they are today.

“Porvenir, Texas” incorporates interviews with family members and experts, as well as dramatizations. “Some of the descendants were present on set for the reenactments,” Shapter recalled. “It was emotional for them, and our cast and crew all felt it.”

The film includes footage of Juan Flores, the only eyewitness to the massacre, who was spared because he was 12 years old.

The Porvenir killings ostensibly occurred as retaliation for cattle raids carried out by Mexicans, yet there is no evidence linking anyone from Porvenir to such incidents. Nor was the Porvenir massacre an isolated event. During the mid-19th century into the early 20th century thousands of men, women, and children of Mexican descent were victims of extrajudicial lynchings and killings in the Southwest. Yet these events remain largely unknown by the public, including Latinos.

Erased from history

According to John Morán González, director of the Center for Mexican American Studies at the University of Texas at Austin, until fairly recently the Porvenir massacre was effectively erased from history. “What made it notable was the number of people killed, and the embarrassment of the state of Texas after the Rangers were implicated.”

None of the Rangers involved in the Porvenir killings were ever prosecuted for their actions.

“There were many cases like Porvenir, where the initial response from the state was to try to fabricate what really took place,” said Monica Muñoz Martinez, an assistant professor at Brown University and the founding member of the public history project Refusing To Forget. “It was not unusual for the state to try to justify such acts, by criminalizing the victims. Residents of Porvenir were described at times as squatters or bandits. None of this is true.”

Back then, it did not matter whether a person of Mexican descent was an American citizen. “Class, social standing, and citizenship were no protection from violence,” Martinez said. Mexican nationals actually had more avenues for protection or redress, because they could appeal to their consul or the Mexican government for help. Mexican Americans, on the other hand, had no one to turn to, as the government did not recognize their legal rights.

While many Americans are familiar with the history of lynchings of African Americans, few are aware of similar acts of violence committed against people of Mexican descent. “It may have to do with the fact that the American conscience is bothered by its ugly chapters of slavery and Jim Crow laws in history,” Emilio Zamora, professor of history at UT Austin, said. “The big problem is that the experience of people of Mexican origin are dismissed or left out of curriculums.”

Not taught in Texas schools

The Porvenir massacre, which is not included in the standard curriculum for Texas history in Texas public schools, remains controversial. Efforts by descendants and historians to obtain a marker commemorating the event took years and resulted in a fight with local leaders opposed to “militant Hispanics” politicizing the tragedy. The marker was finally approved , but with the suggestion that additional markers be considered commemorating violence by Mexicans against white settlers. The Porvenir marker went up in 2018, on a highway outside Marfa, Texas.

For Arlinda Valencia, who maintains a website for Porvenir descendants, the August mass shooting in her hometown of El Paso carried echoes of the violence in Porvenir. “What happened 100 years ago is happening again today. In El Paso, 22 people were murdered because of the color of their skin, in Porvenir it was 15 people. It’s just something that shouldn’t be happening.”

Historians like Muñoz Martínez see parallels between the political environment at the time of the Porvenir massacre and the recent attack in El Paso, where a gunman who later told authorities he was targeting Mexicans left 22 people dead and dozens wounded. Both occurred during a period of anti-Mexican rhetoric, amid tensions along the border and fears of immigrants.

“The El Paso shooter was reportedly worried about Hispanics voting, and changing the state of Texas,” Monica Muñoz Martinez said. “That same sort of rhetoric was used 100 years ago; “illegals voting” is a well-worn historical trope.”

“People say the past is the past, and you’ve got to move on,” Martinez added. “Unfortunately, that is just not the case. Violence against Latinos and fear of Mexicans has become more relevant in the past two years than I ever could have imagined.”

Follow NBC Latino on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram

No comments:

Post a Comment