The political winds are a changin' here in Texas. A number of us opposed these tests from the very beginning and we've worked really hard for over 15 years now to let people know just how harmful they are despite the high-sounding rhetoric of "all children counting" and "leaving no child behind." In 2000, we had a whole federal court case around high-stakes testing and their disparate impact on Latinos, African Americans, special education children and English learners.

The harmful effects were already abundantly clear and in fact found their way into the final ruling by Judge Prado in 2000 (not that we won the case, but rather that the judge actually agreed to the finding of disparate impact).

Dr. Linda McNeil from Rice University and I even "lobbied" in Congress against NCLB in 2002 before it became law. For purposes of clarity, Dr. McNeil and I didn't lobby in the "paid lobbyist" sense in contrast to Kress who got paid handsomely to do so by the testing industry, but rather in the advocacy sense that went beyond us just making a presentation on Capitol Hill which we also did. We were guests of the late Senator Paul Wellstone who welcomed scholars like us from throughout the country to come and tell our Congressional delegations that represent us just how wrong-headed NCLB promised to be. Himself a former professor, as well, Senator Wellstone was equally passionate against the passage of this law, in particular because of its predicted harmful effects against special education children.

Nothwithstanding NCLB architect Sandy Kress' "fears," all national educational research organizations of any repute have denounced our uses of high-stakes standardized testing from the very beginning. It wasn't like it started out kinda' good and ended up being perverse; it was arguably so since the beginning. Or maybe how you saw this system of testing depended somewhat on what side of the testing equation you or your group occupied historically: "High" or "low" achiever.

If these tests were made for you/your group/your zip code, great; if they weren't, it was going to be a hard, long difficult political struggle to get out from under a yardstick that positioned you/your group for the spoils of the system, including tracking, socially constructed failure, low academic self-esteem and the like.

So why all the animus now? Simple answer. Legislative over-reach due to the unabated, unchecked zeal by its adherents that resulted in a ridiculous number of tests—and the fact that what was happening to poor, children of color all along now was impacting white, middle class families whose parents finally decided that enough was enough. (Better late than never.)

Give me a break, Sandy Kress (see his pious rhetoric below), we were not ever—nor are we ever—going to test our way to equity. It woulda' happened by now if so.

Now reducing the number of tests and limiting their (ab)uses in and of themselves will not necessarily engender equity either, but they do limit the negative impacts of an important barrier to it so that we can focus on other things like authentic forms of learning and assessment. Rather than trying to micromanage every minute of their day, we need to actually free up our teachers to impart their craft.

If you want to think of alternatives to the current system and what accountability could be, consider this policy memorandum put together by our students and me from the University of Texas Center for Education Policy: http://tinyurl.com/occ3w6t

Texas and the nation, we do have options and it's way past time that we engage these seriously. Senator Seliger's Senate Bill 149 is a good step in this direction.

-Angela

Education

March 5, 2015 Updated: March 5, 2015 10:10pm

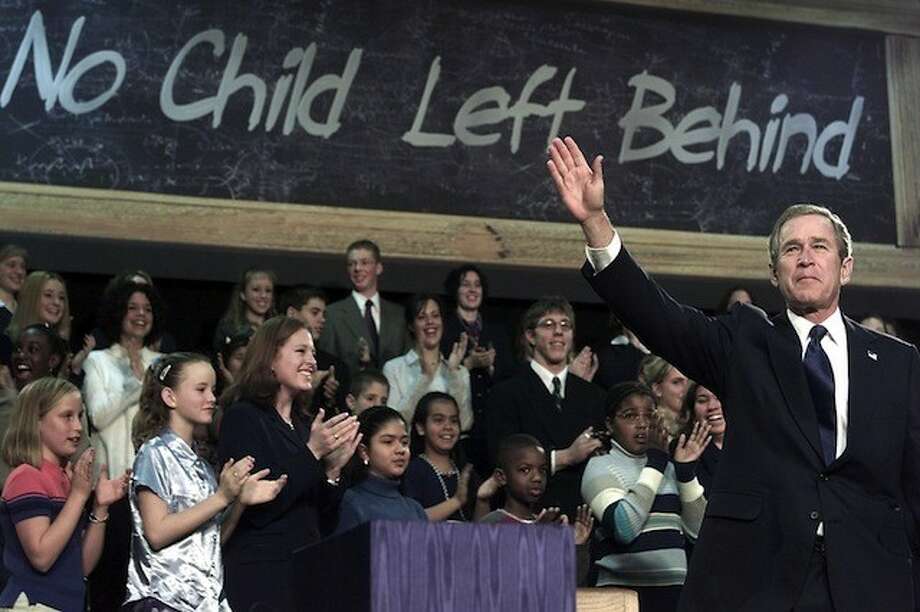

President Bush leans over to speak with third grader Tameron Clark, clasping her hand, as he tours a tutoring center at Kirkpatrick Elementary School in Nashville, Tenn., where he is promoting his "No Child Left Behind" education agenda Monday, Sept. 8, 2003. (AP Photo/J. Scott Applewhite).

Congress is grappling with whether to overhaul or even repeal the 14-year-old law, creating uncertainty in the states about compliance. Federal officials, meanwhile, are considering whether to sanction Texas for failing to comply with federal rules on teacher evaluations.

Dissatisfaction with the law's requirements, and the influence of growing resistance to high-stakes testing among teachers and parents, is palpable at the Capitol. It could lead legislators to reduce state testing requirements to the bare minimum allowed under federal law.

The No Child Left Behind Act of 2001 might live in Washington, but its roots are in Texas.

As governor, George W. Bush advocated for an end to social promotion policies, focused on the importance of early reading ability and strengthened the accountability system put in place by his predecessor, Democrat Ann Richards. By 1999, the New York Times lauded Bush, then a presidential hopeful, as having helped turn Texas' public school system into an "emerging model of equity, progress and accountability."

Eager to carry this mantle to Washington, Bush pitched landmark, bipartisan legislation that would require states to assess children in grades three through eight, and again in high school, and set annual benchmarks. The goal was to bring every student up to grade level by 2014.

Bush called it the "cornerstone of his administration," and it was a truly Texas creation.

"It was the apple of President Bush's eye," said Rod Paige, the former Houston ISD superintendent who helped Bush implement the policy as his first secretary of education.

Original idea altered

Now, however, many Texas leaders want nothing to do with the much-maligned law. That's because the intentions of the original, bipartisan legislation have been lost, said Houston Federation of Teachers President Gayle Fallon.

"It started with a Texas product, but it started with a little more common sense," said Fallon, who said Bush's intent was to target struggling students in disadvantaged groups using diagnostic tools, not high-stakes exams. "It has morphed into a nightmare of test-driven instruction."

Sandy Kress, an architect of the law who was Bush's senior adviser on education in 2001, said he was saddened by the political winds that have Texans, and others, speaking out against No Child Left Behind.

"We're just living in a pretend world that somehow or another we can get away with not being tough enough with ourselves and our kids to get them ready," Kress said, adding that efforts like Seliger's contribute to a "dumbing down" of Texas students. "I think it's bad for the state, and I think we're going to pay a price for it."

Bolstered by the growing anti-testing movement, state lawmakers last session cut the number of end-of-course exams for high school students from 15 to five. Rep. Dan Huberty, a Houston Republican, passed legislation to do the same in grades three through eight, but his bill would have dropped Texas below the minimums required in No Child Left Behind. The Legislature approved the proposals, but the U.S. Department of Education would not give Texas a waiver to cut testing to this extent.

This year, Huberty is trying again.

"We're going to take another run at it," said Huberty, who believes it's time to "completely redo" No Child Left Behind and reduce state exams, known as the State of Texas Assessments of Academic Readiness, or STAAR, tests. "We are continually over-testing our kids. We're creating an atmosphere that is not conducive to learning."

Huberty has filed a bill that would cut STAAR tests in elementary and middle school to the federal minimums and another that would cut them further, eliminating math and reading exams in fourth, sixth and seventh grades.

On the Senate side, Seliger is working to reduce the negative consequences of high school STAAR end-of-course exams. His Senate Bill 149, which is being fast-tracked through the Legislature, would allow some high-achieving high schoolers to graduate even if they don't pass these tests.

Lawmakers still recognize the need for assessments to gauge student learning, said House Public Education Committee Chair Jimmie Don Aycock, R-Killeen.

"I have reached the point that I don't have a high level of confidence in the testing instrument itself," Aycock said. "But I think we have both instructional problems and assessment problems that would be very difficult to work through."

Hurdles await bills

If Huberty's bills pass in the Legislature, Texas again would have to seek approval from Washington for a testing regimen that doesn't meet federal standards. The state is having trouble securing a waiver from No Child Left Behind's mandates based on previously passed laws.

When President Barack Obama took office, the nation was just a few years away from Bush's deadline to have all students reach grade level in reading and math. Concluding this goal was unachievable, the administration took steps to allow states to secure waivers to opt out of the law's achievement mandates.

By 2014, nearly every state had secured one, including Texas. But this year, Texas has had problems renewing its waiver, and negotiations focusing on the state's teacher evaluation system are continuing.

If Texas joins the small pool of states without waivers and Congress fails to strike a deal this year on reauthorization of No Child Left Behind, the state would lose control over how it spends millions in federal dollars for low-income student populations. It also would be subject to federal progress reports, a harsh grading system that teacher groups said would slap "failing" grades on the majority of Texas schools.

No comments:

Post a Comment