It is interesting to consider that the concept of compulsory education together with the idea of "public free" schooling in Texas, the Southwest, and in the U.S., generally, begins with the Spanish during the colonial period. Later, when Texas became a republic, it is noteworthy to consider that it was the Tejanos—and not the Anglos—who advocated for a system of education in the new country. Accordingly,

The irony of all of this is of course the achievement gap and harmful stereotype that Mexican Americans do not value education when the roots for this run deeply in not only a diametrically opposite direction but in one that has had a defining role with respect to the evolution of education in Texas and the U.S., as a whole.

True, our indigenous forbears valued education just as much, but the taking away of their lands and identities undercut tribal governance, including education.

When we speak of the potentially redemptive power of culturally relevant curriculum and Ethnic Studies, these are the kinds of subjugated histories and knowledge that can make a difference for our youth.

Palabra! / In Truth!

Angela Valenzuela

c/s

By Lino Garcia

Tejano Talks

Hispanics have always enjoyed a penchant for education, and especially for endowing their children this love of learning.

Long before Spain began the colonization of the Americas in 1521, it had developed top universities noted for their excellence in all aspects of university life.

During the Middle Ages, King Alfonso X had already outlined the different segments comprising these institutions of higher learning when he wrote his “Las Siete Partidas (The Seven Portions).”

We know that the oldest known university in Spain is the Universidad de Salamanca, which was established in 1218 by King Alfonso IX.

The Universidad de Oviedo was founded in 1608, and offered instructions in Arts, Canon, Law, and Theology to its students.

|

| The Spanish brought to the Americas that penchant for learning first established in the Iberian Peninsula. The Universidad Autónoma de México in Mexico City was established in 1551 by a Royal Decree of King Carlos V. (Photo: Tejano Talks) |

Nursing this love for education in their citizens, the Spanish authorities brought to the Americas that penchant for learning first established in the Iberian Peninsula. We know the Universidad Autónoma de México in Mexico City was established in 1551 by a Royal Decree of King Carlos V, King of Spain and Emperor of the Holy Roman Empire.

It was first known as the Royal Pontífice Universidad de México, and in 1910 became known as the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México or UNAM.

It was first known as the Royal Pontífice Universidad de México, and in 1910 became known as the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México or UNAM.

So, when the call came from the Spanish authorities seeking faculty members and well-trained priests, hundreds of young men left Spain to dedicate their entire lives to establishing schools designed to educate the Native Americans, Spanish soldiers and their children. They followed the Queen Isabela and King Fernando decree that, during the Age of Discovery in the 15th Century, had declared a desire to convert newly discovered civilizations to the “Santa Fe (Holy Faith),” and made them loyal subjects of the Spanish Crown. Thus, were born the Spanish Christian Missions in Texas and other parts of the then Spanish Southwest, where educational components were established.

|

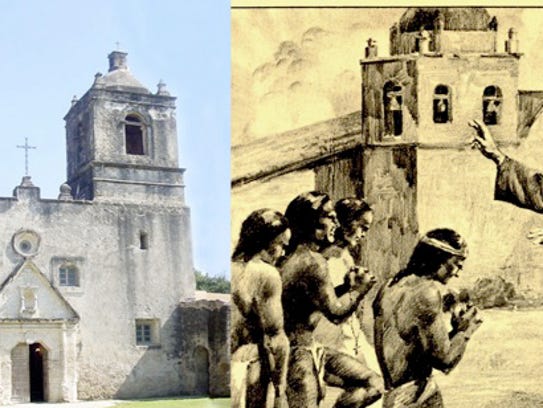

| As the Spanish meandered into what is now Texas, they brought priests who would not only Christianize the Indians but would become the educators of the native tribes of the Lone Star State as well as the children of the Spanish soldiers stationed in missions and presidios throughout the land. From El Paso to San Antonio and La Bahia, education thrived. (Photo: Tejano Talks) |

Max Berger in his “Education in Texas during the Spanish/Mexican Periods” tells us about the efforts by the citizens of Colonial Spanish Texas to establish the first system of public schools. Thus, every mission had as its component an industrial school for instructions in industry and agriculture. The first mission with its educational component was established in Texas in 1690, and within five or more years 25 more were also erected. The first settlement in Texas by Spanish families and soldiers was the founding of San Fernando de Béxar (later San Antonio) in 1718. The first such non-mission school began its operation in San Antonio in 1746. Another such school was opened in San Antonio in the year 1789, but closed in 1792.

In 1802, the Spanish government of Texas called for a school to operate that prescribed compulsory attendance, penalizing parents for any failure to comply, The schools were to be tuition-free with lay teachers, who were to be provided a small salary. That set the stage for the “Public Free Primary School” that Mexican authorities supervised after 1821.

At La Bahía, a soldier named Galán taught a class of 18 children, receiving donations of meat, lard, salt, and the small salary he received as a soldier. It was difficult to sustain an educational system during the turbulent years of unrest between 1810 and 1821, when Texas was also liberated by the Independence Movement — El Grito — of 1810. In 1828, then governor of Texas José María Viesca encouraged parents to send their children to the best schools possible.

Classes were held from 6 to 10 in the morning during the summer, and 7 to 12 in the winter months; with classes held in the afternoon from two to six during the whole year.

The instructor was to open the school with a prayer, and observe religious events. The lessons included the “three R’s,” with lessons in manners, morals and religion. The teacher was hired on a four-year contract at a salary of $500 a year, payable in monthly installments.

These early schools in Spanish/Mexican Colonial Texas existed until the year 1834. A teacher from the north was hired, but was soon released for lack of proper documented passport to be in the Texas of that time. Northerners arriving with Stephen F. Austin after 1821 were required to erect schools in each new colony, and all instructions were to be given in Spanish.

|

| Both Navarro and Seguín attempted to donate thousands of their own land for the purpose of establishing the first university. (Photo: Tejano Talks) |

Early advocates of schools after 1836 were such Tejano patriots as Lorenzo de Zavala, Antonio de Navarro, and Juan Seguín.

It was Zavala who introduted legislation to establish the first system of higher education in Texas.

Both Navarro and Seguín attempted to donate thousands of acres of their own land for the purpose of establishing the first university.

In addition, in the 19th century land-owners — both Hispanic and Anglo — set up schools to educate the children of the vaqueros in the ranchos across Texas.

Despite obstacles encountered in the New World, the Spanish settlers found ways to bring education to all.

Today, Hispanics students make up 52 percent of all students enrolled in Texas public schools, well forecasting the future workforce now taking shape. We can thank the early Spanish/Mexican efforts in establishing institutions of learning that now benefit all Texans.

Lino Garcia Jr. is an eighth-generation Tejano from Brownsville. He holds the chair of Professor Emeritus of Spanish Literature at the University of Texas Rio Grande Valley and is a supporter of the Tejano Civil Rights Museum and Resource Center in Corpus Christi.

No comments:

Post a Comment