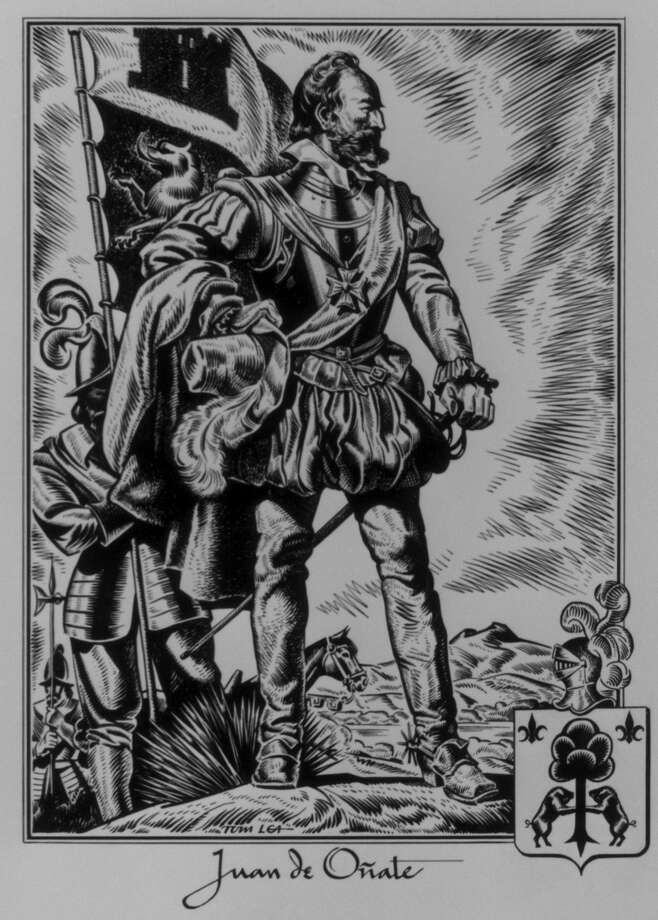

Spanish explorer Juan de

Oñate, in a rendering by El Paso artist Tom Lea, colonized the El Paso

area. Along with Francisco Vasquez de Coronado and Hernando de Soto,

such explorers are given short shrift in U.S. and Texas textbooks.

Oddly, Texas is no longer independent since in 1845 (only a short nine years later), Anglo immigrant insurgents who illegally declared Texas’ independence from Mexico traded their independence to join the U.S. as a slave state.

|

| Photo: /Houston Chronicle |

Likewise, in Texas, most people don’t realize that Sam Houston’s endeavors for Texas independence took over a work in progress. Tejanas and Tejanos had already done the heavy lifting, sacrificing and dying for Texas independence. For example, on April 6, 1813, Texas’ first president, José Bernardo Gutiérrez de Lara, proclaimed the first Texas Declaration of Independence to jubilant Bexareños outside the Spanish Governors Palace. He signed the first Texas Constitution a week later.

The fact is that in rendering overall U.S. history, the roles of Spanish people, places and events, when mentioned at all, are typically distorted, discarded or dismissed.

So, it is with Francisco Vásquez de Coronado (1510-54), a strong courageous leader who figures prominently in the early history of both Texas and the United States. Still, he is often mocked in U.S. history books for what mainstream historians perceive as an outlandish quest, searching for the mythical city of Quivira.

Likewise, students in U.S. classrooms learn about the Spaniards’ lust for gold, search for imaginary places and brutality toward Native Americans. Rarely are they tutored about Spanish explorers’ positive impact in U.S. history.

Based on slanted lesson plans, students are most likely to recall unflattering details, not positive attributes. In fact, the English, Dutch, French and U.S. colonists own a significant share of brutal treatment toward Native Americans.

The fact that Spanish royal and religious leaders forbade ill treatment of indigenous people is well documented. They labored endlessly in attempts to avoid it but were generally hampered by the great distance involved. Many of the more ignoble violators of human rights were arrested, charged with crimes and fairly punished in Spanish courts.

Vásquez de Coronado developed the first detailed exploration reports and the first glimpse of the people, vegetation and terrain of the Southwest (New Mexico), the Texas Panhandle, Oklahoma, Arkansas and Kansas. Attesting to their accuracy, his travel logs were used for years as authoritative documents for later explorers and settlers.

As with other explorers of his day, Vásquez de Coronado was fascinated by a prevailing myth of a mysterious island called Antilia, far into the Atlantic Ocean. Ancient maps even included the site. Supposedly, the Muslim invasion of Spain had caused seven Portuguese bishops to load all they owned in boats, and they sailed off and resettled far away in the sea. As such, when Columbus reached Española in 1492, European experts believed he had reached the Island of Antilia, and so named the group of islands. That name — the Antilles — remains to this day.

Most, if not all, 15th-century Europeans believed in the Antilia legend and the Strait of Anián, along with other legends. When famous explorer John Cabot first landed on the upper eastern shore of America, sailing for the king of England, he named the land “Seven Cities.” He believed he had found Antilia.

In initiating his 1539-40 journey, Vásquez de Coronado, governor of Nueva Galicia, was also hoping to equal the good fortunes of Hernán Cortés and Francisco Pizarro by finding another Aztec empire in the north. After dispatching forward parties, the explorer was encouraged by promising reports. He split up his large expedition, totaling nearly 400 military men, families, more than 2,000 Native American allies, and large herds of horses, cattle and sheep.

This is verified as the first massive movement of Europeans into New Mexico. At times, contact with hostile natives was vicious. Even so, Capt. Garcia López de Cárdenas, leading one of Vásquez de Coronado’s subgroups, was among the first Europeans to see the Grand Canyon.

In 1541, the Spanish traveled through a grassy area they equated with a never-ending sea (Llano Estacado) in northern New Mexico and the Texas Panhandle. Of special note to Texans is the fact that on May 29, 1541, Father Juan Padilla, a priest in the Vásquez de Coronado expedition, offered the first American Thanksgiving Day religious ceremony in the Palo Duro Canyon in the Texas Panhandle. A historical plaque identifies the site.

Although Vásquez de Coronado and Hernando de Soto visited the same region at the same time in Kansas and Arkansas, they missed each other by about 300 miles. Three intrepid Spanish explorers were the first Europeans to travel in today’s middle United States — Vásquez de Coronado, de Soto and Juan de Oñate. Thrown from his horse in 1542, Vásquez de Coronado was greatly limited by his injuries. He returned to Mexico City where his health worsened.

Francisco Vásquez de Coronado died in 1554 at the young age of 44.

Most explorers in America seem to have Spanish rather than English names. When you understand this, you understand that they have earned their place in history. The strong foundation of the authentic story of the U.S. rests on logs and cartography prepared by Spaniards Alonso Alvarez de Piñeda, Estéban Gómez, Lucas Vásquez de Ayllón, Pedro de Salazar, Fortún Jiménez, Juan Rodriguez Cabrillo, Bartolomé Ferrer and so many others.

They merit but rarely receive their fair share of recognition, respect and equal treatment with Anglo Saxon characters in U.S. history books.

It’s time to render U.S. and Texas history in a seamless manner. Mainstream U.S. historians must learn to enfold vital Spanish contributions to our nation’s founding. In Texas, pre-1836 Spanish-Mexican people, places and events must no longer be arbitrarily edited out of Texas history just because they don’t fit the Stephen F. Austin and Sam Houston models.

Likewise, the Texas State Board of Education must stop using 1836 as the Texas history baseline.

Finally, if you want to learn more of the Spanish-Mexican pioneers who founded this great place we call Texas, plan to attend the 38th Texas State Hispanic Genealogical and Historical Conference, Sept. 28-30, sponsored by the Tejano Genealogy Society of Austin, at the Crown Plaza Hotel in Austin.

José “Joe” Antonio López was born and raised in Laredo and is a U.S. Air Force veteran. He lives in Universal City and is the author of four books. His latest is “Preserving Early Texas History (Essays of an Eighth-Generation South Texan).” This article was first published by the Rio Grande Guardian International News Service.

No comments:

Post a Comment