I had forgotten about this piece published back in 2011 in the Journal of Curriculum & Pedagogy. By the way it reads, I almost could have published it yesterday. Thanks to LULAC for this organization's support over the years. We NEED our civil rights organizations still today.

Our work and the struggle continues.

Thanks to Dr. Eliza Epstein for sending it my way.

-Angela Valenzuela

Scholarship and Civil Rights: Claiming a Progressive Voice in Texas Politics and Policy Making Angela Valenzuela

ANGELA VALENZUELA University of Texas at Austin

What is to be done to counter the current conservative political climate and how do we claim a progressive curriculum and pedagogy in our practices? I write from my perspective as a researcher, scholar, and legislative and community activist. Perhaps more through artistry and experience rather than through science or technical know-how, I further combine these roles in my current position as Education Commit-tee Chair of the Texas League of United Latin American Citizens (LULAC), the nation’s oldest and largest Latino civil rights organization (www.TxLULAC.org).

Writing strictly as a scholar, it is tempting to answer this question with an analysis of larger political currents, not the least of which en-tails a serious consideration of minority and majority relations in our state and nation and their significant implications for curriculum, pedagogy, and policy development in these areas. I deploy these concepts of minority and majority not in a numerical sense but rather in the sociological sense of unequal power relations between Anglos and communities of color as reflected in uneven political representation—and thusly, civic participation—at all levels of government and decision-making. This imbalance institutionalizes a tragic divide between actors at the state level where conservative standardization policies originate and the communities and children who are targets or objects of such policies.

As a researcher, I could similarly address the injurious divide between academic researchers and policymakers. To my university’s credit, this concern is echoed in a series of recent introspective and self-critical essays regarding the positive, bridge-building role that a “citizen-scholar” can play in response to pressing policy issues (Cherwitz, 2005).

Stated simply, it matters enormously that university researchers are overwhelmingly ensconced in an ivory tower existence where their accountability is mainly to their profession along an open time frame in which to generate policy relevant results, if at all. In contrast, policy makers are accountable to their constituents and they operate within determinate time frames in which to develop solutions to pressing problems. As a consequence there exists a tragic gap between the academy and policymaking that is nonetheless being filled by mercenary, agendic researchers who work for a massive array of well-funded conservative think tanks that in the area of education seek to discredit and then privatize public schools under the guise of expanding choice to taxpayers (Valenzuela, 2004a; Shaker & Heilman, 2002).

In an absence of both visionary leadership and effective grassroots mobilization, it will be difficult to leverage a significant challenge to this conservative turn in educational politics engendered by the in-creasing influence of both the religious and business right (Valenzuela, 2004a). However, since effective policy development demands a decades-long, committed, political response that civil rights organizations typically embody, I impart my work with Texas LULAC as a model for social action. This activity addresses these two fissures, namely, that between the state and a poor and minority polity whose children are increasingly concentrated in the public school system, as well as that between the academy and policymakers.

As Education Committee Chair of Texas LULAC, I have had the pleasure of organizing several legislative events that have brought university researchers together with legislative staff, teacher associations, and civil rights organizations to discuss issues related to high-stakes testing and student retention. Through our research, presentations, and publications (Valenzuela, 2002, 2004b), we have made the case that when the test is the sole or primary arbiter in decisions with such long-lasting consequences for children, they have a right to be assessed in a complete and fair manner. This has translated into a legislative remedy that calls for the use of as many criteria as may reasonably indicate children’s cognitive abilities and potential whenever making high-stakes decisions like graduation/non-graduation or promotion/retention in grades 3, 5 and 8 (the state’s new retention policy went into effect in 2003).

Although for the past two legislative sessions our proposed legislation has been quite specific, it addresses the linchpin of the accountability system—student testing. It should be noted that despite support for the legislation in the Texas House of Representatives, we have encountered political roadblocks with the current and previous chairs of the House Committee on Public Education. As scholars, we nevertheless remain resolute that children are entitled to fairness and validity in assessment. Indeed, this position flows directly from our review of the evidence, including that provided by the state itself.

As observers of the inner-workings of the accountability system, we further contend that the testing system is performing two incompatible functions in one (McNeil and Valenzuela, 2001). That is, it doubles as both an “assessment” (testing) and “monitoring” system. Particularly in poor and minority schools that are subject to the “gaze” of central office, numbers-based accountability manages the behavior of the adults in the system by pressuring them to perform. The rhetoric gives the impression that all children are finally being taught; however, the reality is that this edict often translates into dumbed-down routinized pedagogy with disastrous implications for student learning and growth. This conflation of functions logically corrupts the assessment since official test results do not control the extent of coaching, cheating, or the marginalizing of those youth who become liabilities under the cur-rent design. By utilizing a more robust evaluation process, our pro-posed multiple criteria legislation addresses this built-in problem of test validity while promising fairness in testing children when so much is at stake to them personally.

Politically, LULAC has been engaged in a protracted effort to educate its base about the harmful effects of high-stakes testing. Our success is evident in the fact that assessment is at the top of our 2005 legislative agenda. Just as importantly, LULAC also spearheads a multi-ethnic, statewide coalition of university faculty, graduate students, and grassroots advocates for fairness and validity in assessment (www.texas-testing.org). Accordingly, we prepare for and plan press conferences, lobby days, television and radio spots, opinion-editorial pieces, and public forums at the grassroots level.

To conclude, there is much that we as citizen-scholars can do to address the deep and deleterious divides that impact both public life and the development of policy. However formidable the opposition may be, I consider it an extraordinary privilege to both chronicle and par-take in the moment. Indeed, the very act of standing up to injustice is to savor the seeds of triumph.

References

Cherwitz, R. (January/February 2005). Citizen-scholars. The Alcalde, 50–60.

McNeil, L. & Valenzuela, A. (2001). The harmful impact of the TAAS system of testing in Texas: Beneath the accountability rhetoric. In M. Kornhaber & G. Orfield (Eds.), Raising standards or raising barriers? Inequality and high stakes testing in public education (pp. 127–150). New York: Century Foundation.

Shaker, P. & Heilman, E. E. (2002, January). Advocacy versus authority: Silencing the education professoriate. Policy Perspectives, 3 (1), 1–6.

Valenzuela, A. (2004a). Accountability and the privatization agenda. In A. Valenzuela (Ed.), Leaving children behind: Why ‘Texas-style’ accountability fails Latino youth. New York: State University of New York Press.

Valenzuela, A. (2004b). The accountability debate in Texas: Continuing the conversation. In A. Valenzuela (Ed.), Leaving children behind: Why ‘Texas-style’ accountability fails Latino youth. New York: State University of New York Press.

Valenzuela, A. (2002). High-stakes testing and U.S.-Mexican youth in Texas: The case for multiple compensatory criteria in assessment. Harvard Journal of Hispanic Policy, 14, 97–116.

Angela Valenzuela is a professor at the University of Texas at Austin and the Education Committee Chair of the Texas League of United Latin American Citizens

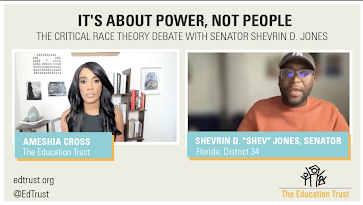

Great discussion between Ed Trust's Ameshia Cross and Sen. Shevrin D. "Shev" Jones, Florida District 34. This show reminds me of how Texas and Florida need to get together and talk. Our battles are so similar.

Great discussion between Ed Trust's Ameshia Cross and Sen. Shevrin D. "Shev" Jones, Florida District 34. This show reminds me of how Texas and Florida need to get together and talk. Our battles are so similar.