This is a central epistemological standpoint for Native peoples, that is, that Earth, Mother Earth, is a sentient, living organism (also read: The Earth is a Sentient Living Organism), a not-so-radical notion the pandemic has perhaps made clear. Little different from viruses and bacterias that help constitute the building blocks of life as we know it, we are all a part of Earth and the cosmos and our evolution as homo sapiens is entwined with Her, with Gaia, and the cosmos. What a profound thing to contemplate.

Lovelock is clearly a rock-star centenarian, geophysiologist. Although he has very interesting potential solutions to climate warming, I am skeptical about his optimism in Artificial Intelligence (AI), particularly cyborgs' expected capacity to avert humans' species extinction. I would much rather that we pay attention for once to our Indigenous elders who still have the wisdom and knowledge for humans' self-preservation.

For example, read this encouraging NPR piece out of California in the wake of the state's devastating fires: California Teaming Up With Native American Tribes To Prevent Wildfires.

These measures of teaming up with Native peoples must be taken up everywhere globally and not in a way that appropriates Native knowledge, but in a way that humbly and respectfully includes them, in partnership, as full-fledged partners to the solutions of an Earth that is severely out of balance.

Great food for thought on a Sunday morning.

-Angela Valenzuela

James Lovelock at 100: the Gaia saga continues

Tim Radford reassesses the independent scientist’s groundbreaking body of writing.

by Tim Radford | Nature.com

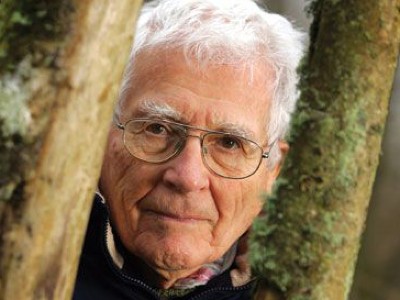

James Lovelock proposes that Earth will be saved by artificial intelligence.Credit: Tim Cuff/Alamy

James Lovelock will always be associated with one big idea: Gaia. The Oxford English Dictionary defines this as “the global ecosystem, understood to function in the manner of a vast self-regulating organism, in the context of which all living things collectively define and maintain the conditions conducive for life on earth”. It cites the independent scientist as the first to use the term (ancient Greek for Earth) in this way, in 1972.

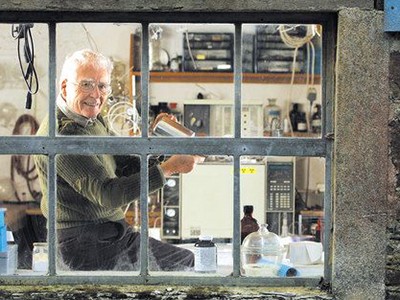

On 26 July, Lovelock will be 100; his long career has sparkled with ideas. His first solo letter to Nature — on a new formula for the wax pencils used to mark Petri dishes — was published in 1945. But, unusually for a scientist, books are his medium of choice. He has written or co-authored around a dozen; the latest, Novacene, is published this month.

As that book’s preface notes, Lovelock’s nomination to the Royal Society in 1974 listed his work on “respiratory infections, air sterilisation, blood-clotting, the freezing of living cells, artificial insemination, gas chromatography and so on”. The “and so on” briefly referred to climate science, and to the possibility of extraterrestrial life. The story of Gaia began with a question posed by NASA scientists while Lovelock was a consultant at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California. That is, how could you tell if a planet such as Mars harboured life?

Final warning from a sceptical prophet

With microbiologist Lynn Margulis, Lovelock published a series of papers on the subject. In 1974, they developed a view of Earth’s atmosphere as “a component part of the biosphere rather than as a mere environment for life” (J. E. Lovelock and L. Margulis Tellus 26, 2–10; 1974). Earth’s atmosphere contains oxygen and methane — reactive gases, constantly renewed. That disequilibrium radiates an infrared signal, which Lovelock later described as an “unceasing song of life” that is “audible to anyone with a receiver, even from outside the Solar System”. Thus, the answer to NASA’s question was already written in the static Martian atmosphere, composed almost entirely of non-reactive carbon dioxide.

That was the beginning of a sustained and developing argument, in the face of sometimes dismissive criticism, that recast Earth as, in effect, a superorganism. Lovelock’s Gaia theory states that, for much of the past 3.8 billion years, a holistic feedback system has played out in the biosphere, with life forms regulating temperature and proportions of gases in the atmosphere to life’s advantage. Earth system science is now firmly established as a valuable intellectual framework for understanding the only planet known to harbour life, and increasingly vulnerable to the unthinking actions of one species. Colleagues and co-authors acknowledge that the argument continues, but endorse the importance of Lovelock and Margulis.

Entwined evolution

“The insight that the oceans and the atmosphere are thoroughly entwined with the living biosphere, and must be understood as a coupled system, has been completely vindicated,” says marine and atmospheric scientist Andrew Watson of the University of Exeter, UK. Lee Kump goes further. “Lovelock also showed us that Darwin had it only half right,” says Kump, a geoscientist at Pennsylvania State University in University Park. “Life evolves in response to environmental change, but the environment also evolves in response to biological change.” Despite severing formal links with universities decades ago, Lovelock has been showered with honorary degrees and awards from bodies as varied as NASA and the Geological Society of London.

The procession of engaging books began in 1979 with Gaia: A New Look at Life on Earth. Each volume made its case more forcefully than the last, exploring what was known first as the Gaia hypothesis, then simply as Gaia, and the hazards facing either the biosphere or humanity. The books include his endearing autobiography Homage to Gaia (2000), increasingly urgent warnings of climate devastation in The Revenge of Gaia (2006) and The Vanishing Face of Gaia (2009), and the less apocalyptic A Rough Ride to the Future (2014).

James Lovelock pictured in 1989.Credit: Terry Smith/The LIFE Images Collection/Getty

Novacene picks up from that note of hope, and showcases another big idea. Gaia might, after all, be saved — by the singularity. This artificial-intelligence takeover, which so alarms many doomsayers, will be our redemption. Lovelock argues that increasingly self-engineering cyborgs with massive intellectual prowess and a telepathically shared consciousness will recognize that they, like organisms, are prey to climate change. They will understand that the planetary thermostat, the control system, is Gaia herself; and, in tandem with her, they will save the sum of remaining living tissue and themselves. The planet will enter the Novacene epoch: Lovelock’s coinage for the successor to the informally named Anthropocene.

Lovelock welcomes this. “Whatever harm we have done to the Earth, we have, just in time, redeemed ourselves by acting simultaneously as parents and midwives to the cyborgs,” he writes. He takes the long view on this rescue, however. Climate change is a real threat to humanity, but Earth will inevitably be overtaken by a ‘big heat’ in a few billion years, as the Sun slowly waxes more fierce.

Although co-authored with journalist Bryan Appleyard, Novacene reads like undiluted Lovelock. From the start of his writing life — no matter how tortuous the narrative or complex the argument — Lovelock has written persuasively. In his debut, Gaia, he sidestepped evolution’s first and biggest obstacle (how to get from organic chemistry to a living, devouring, excreting, replicating organism) in two sentences that seem to me models of clarity and brevity: “Life was thus an almost utterly improbable event with almost infinite opportunities of happening. So it did.”

No place like home

In The Ages of Gaia (1988), a richer and more closely argued restatement, he answered the vexed question of how life contradicts the second law of thermodynamics. Life, he wrote, “has evolved with the Earth as a highly coupled system so as to favour survival. It is like a skilled accountant, never evading the payment of the required tax but also never missing a loophole.” This metaphoric brilliance is no rarity. A few pages on, he reminds us that Gaia is “a quarter as old as time itself. She is so old that her birth was in the region of time where ignorance is an ocean and the territory of knowledge is limited to small islands, whose possession gives a spurious sense of certainty.”

Lovelock’s Gaia theory is only one aspect of his nonconformism. His vigorous support for nuclear power annoys many environmentalists. Brought up as a Quaker, he registered as a conscientious objector in 1940, then changed his mind and prepared for military action in 1944 (the National Institute for Medical Research in London considered him more useful in the lab). Later, he became a consultant for the security services of Britain’s defence ministry. Among his inventions is an electron capture detector sensitive enough to identify vanishingly small traces of pollutants — such as the pesticides that spurred Rachel Carson to write the 1962 book Silent Spring — and chlorofluorocarbons, later implicated in damage to the ozone layer. In Novacene, he writes teasingly that he now sees himself as an engineer who values intuition above reason.

Lovelock to the last, he even has a kind word for the Anthropocene, marked by degradation of natural resources and the devastation of the wild things with which humanity evolved. He gives a “shout of joy, joy at the colossal expansion of our knowledge of the world and the cosmos”, and exults that the digital revolution ultimately “empowers evolution”. Is he right? Some of us might live to find out. In the meantime, if you want a sense of hyperintelligence in bipedal form, Novacene is a good place to start.