I am so happy to learn about this Austin teacher, Lorena Germán, who, like many of us in this nationwide movement, is taking up the cause for Ethnic Studies by bringing more culturally relevant texts into the classroom. She says, and I fully agree, that "curriculum is at the root of what’s commonly termed 'difficult schools' — 'you continue to teach a culturally distant curriculum, and, all of a sudden, students are the problem.'”

Spot on. Do read her piece, but also be mindful of an array of resources at your disposal.

My favorite go-to place for learning about children's books is the Cooperative Children's Book Center out of the University of Wisconsin. They have great information on African American, Latina/o/x, and Native American texts. They also have a great blog on children’s books that you can peruse. You could reach out to them directly with any additional information or questions that you seek or have. I recently corresponded with folks at “CCBC Info ccbcinfo@education.wisc.edu They are hugely influential and authoritative in this arena.

For bilingual or emergent bilingual children, you will also want to, check out Colorín Colorado: A bilingual site for educators and families of English language learnersFor Native Americans, I just found this great resource: 40 Children's Books Celebrating Native American and Indigenous Mighty Girls. Here’s a great listing of Aztec children’s books, too.

For African American children’s books, the Coretta Scott King Award mentioned above is excellent. Please also see the following wonderful websites:

For small children, a place to start might be the National Association for the Education of Young Children. I also think that teachers would do well to learn about the field of multicultural education itself. Rethinking Schools out of Milwaukee has been addressing for some time now anti-racist, inclusive curriculum. For example, this text title, Rethinking Multicultural Education is an excellent resource for getting a sense of what the range of concerns are within the field of multicultural education.

Enjoy!

-Angela Valenzuela

#DisruptTexts

Asher Price Austin American-Statesman | USA TODAY NETWORK

Lorena Germán, an Austin teacher who has worked to revamp the traditional English class reading list, has a saying: “It’s one thing to take candy from a baby. It’s another to take a classic text from an English teacher.” h As a member of the collective #DisruptTexts, Germán is on the vanguard of a national reexamining of classroom book lists, one that presses teachers to set aside the stalwarts of the Western canon in favor of more contemporary, diverse authors.

The struggle over which books are taught in classrooms has raged for generations, part of the broad culture wars that have engulfed the nation. But in the wake of the Black Lives Matter protests, a Trumpist backlash and a general reckoning by institutions about race, the debate has renewed urgency.

#DisruptTexts focuses on “challenging the canon” through posts on social media and through professional organizations, Germán told the American-Statesman.

“We want to talk less about what not to teach and more what to teach, to expose teachers not only to great new voices, but also how do we teach them meaningfully, and how do we teach books in new and refreshing ways,” said Germán, who taught English at Headwaters School, a private school with campuses in South Austin and downtown, for five years — and now, amid the pandemic, looks after her three children at home.

Germán and her collaborators — teachers in Pennsylvania, Massachusetts and Colorado — have faced resistance from educators and others, including death threats.

“For some teachers, the classic texts function as Confederate statues,” she told the Statesman. “There’s a nostalgia attached to them,” she said, partly because the books were so important to their own formation as students and teachers.

With incredulity, she recounts that at one school where she was doing work, she learned that a teacher had been teaching the same book — “The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn,” Mark Twain’s ironic examination of race and slavery told through the eyes of a young runaway teen — for 24 years.

“There’s no other book merits space in your curriculum to address those issues?” Germán said.

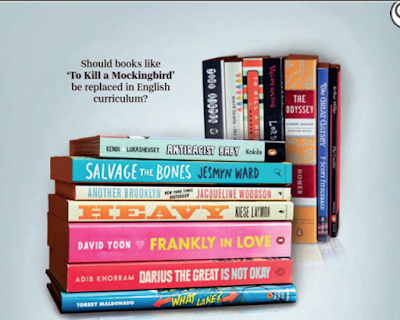

She recommends, instead, Kiese Laymon’s memoir “Heavy,” Colson Whitehead’s “The Underground Railroad,” or books by Zadie Smith, Elizabeth Acevedo and Jacqueline Woodson, among others.

Another mainstay she has suggested should occasionally be left off reading lists: “To Kill a Mockingbird.”

Germán herself has taught the classic, she wrote on the #DisruptTexts website.

“I do so because I have a predominantly white group of students who have often already heard of it, some who have read it, and many whose parents have idolized it,” she wrote. “I use it as an entry point to engage them in critical anti-racism dialogue. It’s an entry point because it’s familiar, it doesn’t feel intimidating for them, and it connotes comfort and nostalgia.”

But with Black characters in the classic book “mistreated, misunderstood, underrepresented,” she suggests as an alternative Angie Thomas’ book “The Hate U Give.”

There is no sacred cow, for her, in the English reading list. About Shakespeare, she wrote on Twitter: “Trust me, your kids will be fine if they don’t read him.”

She suggested as alternatives or companions to mainstay Shakespeare plays Amiri Baraka’s “The Dutchman,” Zora Neale Hurston’s “Color Struck,” Ntozake Shange’s “For Colored Girls Who Have Considered Suicide/When the Rainbow Is Enuf,” and Athol Fugard’s “Master Harold and the Boys.”

Part of the challenge with remaking curricula, she said, are the teachers and administrators themselves.

“There aren’t enough teachers of color in the English field,” she said.

That fact is compounded by a gender dynamic within schools, between teachers — who tend to be women — and administrators, who tend to be men, she said, putting up further roadblocks to schools diversifying their curricula.

Embedded in the pushback she faces, she said, “is fear of other, a fear of losing power.”

Citing the work of Ibram X. Kendi, she said schools should “practice antiracism to create balance” in their curriculum, actively looking for ways to remake what they teach.

“One week if all I eat is red meat,” she said by way of analogy, “then maybe I should aim to eat some white meat and some veggies.”

‘Do you have to teach this text — why?’

In 2018, she co-founded #Disrupt-Texts to help “teachers build a community and find alternatives to the white male-dominated literary canon,” said Germán, who chairs the National Council of Teachers of English’s Committee Against Racism and Bias in the Teaching of English.

The foursome behind #DisruptTexts does much of its work over Twitter, asking questions about a selected canon stalwart so that teachers, librarians and writers can weigh in. Books they have focused on include “To Kill a Mockingbird,” “Lord of the Flies,” “The Great Gatsby” and “The Crucible.”

The questions they begin with are open ended: “For what reasons might teachers include this text in their curriculum? What is the value in teaching this text? Do you have to teach this text — why?”

The discussion then moves to how to teach the books in ways that bring in marginalized perspectives — or which alternative texts could be employed instead.

This work sometimes has led to threats.

“Did y’all know that many of the ‘classics’ were written before the 50s?” Germán wrote on Twitter on Nov. 30. “Think of US society before then & the values that shaped this nation afterwards. THAT is what is in those books. That is why we gotta switch it up. It ain’t just about ‘being old’” In response, young adult author Jessica Cluess called Germán an “idiot,” arguing that writers like Nathaniel Hawthorne wrote works criticizing the very societies in which their novels took place.

“This anti-intellectual, anti-curiosity bullshit is poison and I will stand here and scream that it is sheer goddamn evil until my hair falls out,” Cluess wrote. “I do not care.”

A day later, Cluess deleted the tweets and apologized — still, her agent soon dropped her for what he called “condescending and personal attacks” by his former client.

But after a Wall Street Journal columnist picked up the cause last month — arguing that #DisruptTexts was a “sustained effort” to “deny children access to literature” and that “critical-theory ideologues” are “purging and propagandizing against classic texts” — Germán began to receive vile notes.

“We need to bring back the KKK and start eradicating you filthy third world commie cretins,” read the printable part of one she shared with the Statesman. The email went on to threaten her family.

In light of the episode, #DisruptTexts released a statement this month: “We do not believe in censorship and have never supported banning books. To claim otherwise is outright false. It is a mischaracterization of our work made to more easily attack us, serve an agenda, and discredit the need for antiracist education.”

The statement also reads: “We believe that no curricular or instructional decision is a neutral one. For too long, the traditional ‘canon’ — at all grade levels — has excluded the voices and rich literary legacies of communities of color. This exclusion hurts all students, and especially students of color.”

Gaining ground

The State Board of Education, which gives direction to Texas public schools, last adopted revisions to the standards for Reading-Language Arts in 2017. The standards do not include literary titles or specific required or recommended books, but do require that students recognize and analyze “literary elements within and across increasingly complex traditional, contemporary, classical, and diverse literary texts.”

“To be clear, decisions regarding specific reading lists or texts is under local school district discretion for all grade levels,” agency spokesman Frank Ward said.

The Austin school district does not provide mandatory reading lists to schools, but its teachers are encouraged to make diverse texts available to students.

Teachers often will offer students a half-dozen texts under a theme — say, the hero’s journey — that might range from a classic to a graphic novel, said Jessica Jolliffe, the district’s assistant director of humanities.

“We’re trying to get texts in front of students that provide them with a balance between what they might need” — such as the canon, ahead of college, Jolliffe said — “and more contemporary writers that address the same themes, even if they might not have been in place long to truly be considered a classic.”

Some teachers across the country have taken the #DisruptTexts conversations to heart.

“I stopped teaching To Kill a Mockingbird and now focus on Born a Crime by Trevor Noah and Dear Martin” — a novel by Nic Stone, wrote @nicblagal, based in Illinois, on Twitter. “Swimming in whiteness my whole life made me think ‘core texts’ should be old texts (awful, I know). But now that #disrupttexts helped me know better, I do better.”

A Houston teacher named Sarah Suggs said she first came across #DisruptTexts as an elementary curriculum coach.

“I became much more aware of who was writing the texts I consumed and recommended,” she wrote.

She continued, “Now that I teach (high school), I am working on curating a variety of representative texts to use in my teaching, as well as make available in my classroom library.”

Fort Worth-area teacher Ale Checka wrote: “I had always been a ‘read classics, but read them critically’ person. I also like paired texts. But bc of DT, I begged for and got a class set of The Crossover” — a verse novel about a pair of basketball-loving brothers — “and it has turned so many kids into poetry and books in verse. Also just renewed/refreshed my teaching practice.”

Teaching empathy Germán, who was born in the Dominican Republic, moved at age 4 with her family to an immigrant community north of Boston.

The predominantly white teachers at her public high school were distant from, even hostile to, their students — mocking them, screaming at them — in ways that started with the curriculum, which was “disengaging us,” she said.

She said curriculum is at the root of what’s commonly termed “difficult schools” — “you continue to teach a culturally distant curriculum, and, all of a sudden, students are the problem.”

After college in Boston, she returned to teach at the very same public school — and from the perspective of the teachers’ lounge was further struck by the metaphorical distance between pupils and teachers.

Eventually, with a master’s degree from Middlebury College’s Bread Loaf School of English in hand — one that involved critical thinking about the classics she now wants teachers to set aside — Germán and her husband, a school administrator, moved to Austin, in search of warmer weather and new school opportunities.

They both ended up at Headwaters School.

“In my class, we’re going to talk about social issues, and we’re going to think about this literature in context,” she said. “We won’t have these books on a pedestal, untouched.”

Reading a range of books by diverse authors is key to encouraging students to think empathetically, which, she said, is an important skill in contemporary America, divided, as it is, along racial and other fault lines.

Kyle Rittenhouse, the 17-year-old who stands accused of shooting three Black Lives Matter protesters in Kenosha, Wis., last summer, “was just in someone’s classroom,” she observed in an interview. “How is that curriculum implicated?”

As for the resistance that she meets, she hears a tone of implicitly racist condescension — critics appear to assume, wrongly, that she hasn’t read Shakespeare or Chaucer, for example — as well as a lack of self-awareness.

“How can people say they are well read when they can go through life and not read a black author?” Germán said.

She and her husband also run the Multicultural Classroom, a consulting agency that has done work for companies like Deloitte — helping them design curriculum to encourage equity and support diversity among their staff — and the Ann Richards School for Young Women Leaders.

A workbook she has written — “The Anti-Racist Teacher” — has made its way into the hands of English teachers at area high schools, as well as to Stephanie Hawley, the official in charge of diversity strategy at the Austin school district, she said.

(A message left with Hawley was not returned.) “We have to change things if we want to see different results,” Germán said. “If the United States reckons with who we are, we have to figure out how we got here — we have to have this conversation.”

Questions for teachers

When educators are looking to evaluate the relevance of canonical works and their place in today’s classrooms, they can consider these questions, according to the #DisruptTexts group:

• Whom does your curriculum center? What identities or voices are marginalized or erased altogether?

• What are the norms and values of your community? How can you problematize or push back against them to expand the worldview of students and young people in it?

• What new knowledge will teachers and students need to critically examine themselves and your chosen text?

• How will the text you’ve chosen amplify and center the work of living creators so that students can see themselves?

• What will you need to unlearn (what assumptions or understandings can you let go of) to make room for new knowledge?

4 traditional books and alternatives

Here are some books #DisruptTexts has examined — and alternatives or companion texts or films that have emerged through ensuing Twitter discussions or on like-minded discussions such as “Fire the Canon”:

• “To Kill a Mockingbird”: Black characters in Harper Lee’s novel are “mistreated, misunderstood, underrepresented,” Germán writes. Atticus Finch “continues to be problematic and so many white people don’t want to admit it. His advocacy has limits. He’s not willing to question the very system that has allowed Tom to end up in this racist situation. In the face of pure racism and bigotry he doesn’t see the need to publicly disrupt the legal system.” As part of the Twitter dialogue, some educators suggested Angie Thomas’ “The Hate U Give.” Bryan Stevenson’s “Just Mercy: A Story of Justice and Redemption,” Ava DuVernay’s film “13th,” or the 1996 movie “Sling Blade.”

• “Lord of the Flies”: The 1954 novel about a group of schoolboys marooned on an island “is a masterful fictional take on how societies are built and broken—if you happen to look like the people in charge of society already,” website Electric Literature posited as part of its Fire the Canon series. “What would happen if not everyone on that island was a prep-school white boy?” Alternatives include “Damselfly” by Chandra Prasad, “Gorilla, My Love” by Toni Cade Bambara, “The Power” by Naomi Alderman, and “Severance” by Ling Ma.

• “The Great Gatsby”: Often described as the great American novel, but “if the novel represents anything, or anyone, it’s a very small, narrow view of what it means to be American,” Tricia Ebarvia of #DisruptTexts has written. As a historical document, the book gives a skewed sense of the period, one teacher wrote in a #DisruptTexts Twitter chat. “My students come in with this idea that the Roaring 20s was a gas,” social studies teacher Jennifer Phillips wrote. But “what (students) don’t know about the 1920s, more often, is the nativism, the visibility of the Ku Klux Klan, the lynchings, the race riots” or “about the eugenics movement born right here in the United States.” Alternatives or companions include “Their Eyes Were Watching God” by Zora Neale Hurston, “Raisin in the Sun” by Lorraine Hansberry, Ernesto Quiñonez’s “Bodega Dreams,” “Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom” by August Wilson, the film “Get Out” by Jordan Peele, “Passing” by Nella Larson, “Cannery Row” by John Steinbeck, “The Bluest Eye” by Toni Morrison, “You Bring the Distant Near” by Mitali Perkins, and “I Am Not Your Perfect Mexican Daughter” by Erika Sanchez.

• The Arthur Miller play “The Crucible,”

a moral examination of truth and propaganda was criticized by #DisruptTexts member Julia E. Torres as “one of too many pieces of canonical literature that disproportionately center the white, Christian, male perspective. More critical discourse comes through discussing Arthur Miller’s caricature of Blackness with the character Tituba, an enslaved woman accused of witchcraft, and the problematic way in which Indigenous people on whose land the play’s action takes place, are essentially absent from the narrative.” Alternatives or companions include Ntozake Shange’s play “For Colored Girls Who Have Considered Suicide/When the Rainbow Is Enuf,” “What Would Crazy Horse Do” by Larissa FastHorse, and Benjamin Benne’s “Alma (or #nowall).”

“How can people say they are well read when they can go through life and not read a black author?”

Lorena Germán

English teacher and co-founder of Multicultural Classroom