Super-important read by Dr. Cesar A. Cruz who

reflects on the way that that Hollywood and the film industry, in general,

encourages deficit notions that black and brown children need (white) saviors , exposing a narrative this is not only patronizing

but also beneficial to a profession that is largely comprised of white educators.

I

hope that his gut-wrenching honesty as a former male teacher of color helps

others to be similarly reflective. Dr. Cruz comments as follows:

That’s why I am now in savior’s complex and poverty porn

rehab. I am currently not teaching students anymore. I don’t deserve to.

Honestly, I wish a lot of people would leave the profession, at least long

enough to self-reflect. I have a lot to unlearn before I get the privilege to

be with students again. I am now on a listening campaign as I hear from

hundreds of students throughout the country who are telling me how deeply they

have been scarred by school.

Thanks for the shout out, Cesar! And thanks for sharing. We have all been touched in some form or

fashion by this highly problematic narrative to which really any of us are

susceptible. That why we all gotta’ get

woke!

Angela Valenzuela

c/s

Being an educator

who is now trying to unpack my savior complex issues, has become my life’s

calling, but it wasn’t always like that. Along the journey, I think I may have

done more harm as an “educator” than good. I would never really want to admit

that though. I try to explain it away by stating that I had good intentions,

but there’s that one saying, about a certain road being paved (to hell) with

good intentions, do you know which one I’m talking about? I laid a lot of

bricks on that road, and so have many of my colleagues, especially the ones

that society deems “educational leaders.”

Over time, as an

“educational leader,” I have learned that if I only look through my intentions,

and not my impact, I am not taking responsibility for all of my actions, and

it’s based on that, that I can be self-critical, realizing that most of my

career I have actually done more harm than good. Here’s how it may have

possibly started for me, but maybe it goes further than that.

Jaime Escalante,

but the one played by Edward James Olmos, in the 1980s educational film “Stand

and Deliver,” was my shining example and hero. I thought that film was right

on. A Latino educator who believes in his students and prepares them for the

greatness that’s already inside of them, what’s not to like about that? As I

look back on the impact that “Stand and Deliver” had on me, I now realize that

I have seen over 20+ films that appear to have the same story of a broken

neighborhood and a hero educator. Even in that poster I was being set-up; “The

school. The teachers. The Parents. The Students. No one cared, except one man.

He was the new math teacher.”

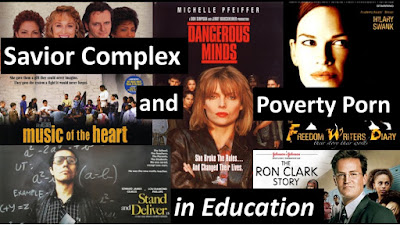

Now I’m starting

to feel duped. However, I must admit that having a Chicano, Raza or Mexican

American teacher is somewhat rare for Hollywood. Most of the time the change

agent is a white teacher, whether in “Freedom Writers Diary,” “Dangerous

Minds,” “Music of the Heart,” “The Ron Clark Story,” “The Principal,”

“Blackboard Jungle,” “McFarland USA,” or whatever the latest “inspirational”

educational propaganda film will air next.

I hate to admit

it, but all of these films pulled at my heartstrings. Sure, there was a part of

me that was deeply critical of the white savior coming into the hood to “give”

the kids hope, but somehow, I found myself always going to see these films.

These educators found a way to somehow create “for them,” “those kids,” a “safe

space” that they (supposedly) “wouldn’t have otherwise,” to help them see

what’s already inside of them, their brilliance, because apparently only this

teacher or leader can. However, that film, like most of Hollywood’s

“educational” films, offer two critically important narratives that would live

in my subconscious for almost 15 years as an “educator;” 1. the broken barrio

or hood, where no one seems to care but the educator. It paints and focuses on

broken windows. For every film to be successful, you have to include some of

the following ingredients: kids of color and maybe some poor whites, graffiti,

broken windows, gangs, guns, drive-bys, drugs, a pregnant teen, a parent in

jail, struggling families (referred to as broken), a dysfunctional school,

multiple forms of abuse, a feeling of being trapped, very little historical

context, and a “no way out” plot line. Then you are ready for narrative number

2: the teacher as hero. These films position teachers as saviors, givers of

hope, counselors, mentors, surrogate parents, cheerleaders, and everything in

between. If it wasn’t for them, “these kids” would probably die. These

narratives create the need for organizations like Teach for America, or

educational reform organization fill-in-the-blank, to exist. It also becomes

addicting for us to keep immersing ourselves in this type of educational

poverty porn, stuff I know I shouldn’t be watching but they got me hooked like

a fiend. I’m stuck watching films that paint neighborhoods a certain way, from

reservations to rural towns, where the conditions are destitute, and in need of

saviors with “lesson plans.” I wish this was only limited to films, but it

lives everywhere, from grad school texts, to educational “research” findings.

Since birth, we

are raised in this society to become heroes. So, I suppose that deep down I

wanted to be that hero that this US society values so much in the form of the

Lone Ranger teacher who shows up to a “broken” school and a “broken”

barrio/hood and saves the educational day. The hero narrative, however, goes

far beyond education. As a matter of fact, it is mostly white heroes who save

us on the movie screen from pretty much everything, including outers space

aliens. White people are pretty amazing as Hollywood myths, but historically,

as educators, many of them have operated with a well-articulated savior’s

complex, whether they know it or not. Many educators and most schools mentally

lynch our students in so many different ways. It is the late educator Dr.

Carter G. Woodson who stated that “as another has well said, to handicap a

student by teaching him that his black face is a curse [with almost no mirrors

in books about who they are, their beauty and contributions] and that his

struggle to change his conditions [by not being able to fully take on white

supremacy, patriarchy and capitalism] is hopeless, is the worst sort of

lynching.” We lynch minds every day in most schools, and yet no-one waves a

flag outside the school, “a child’s mind was lynched today,” but we sure to do

pathologize them when they “dropout.”

Many educators of

color, who fail to see the savior complex within, the whiteness as a norm, do

just as much, if not more damage to our communities, as they become the

enforcers of white supremacy.

I honestly really

struggle to admit that I, a Mexican migrant, man of color, self-identified

“social justice educator,” am a perpetrator of the savior’s complex. I am.

As I find myself

in a self-imposed savior’s complex rehabilitation clinic, I must admit that I

fell into the trap of becoming a shining armor educator that comes to save the

day. How could I let that happen and is this just about individual educators

making that so-called decision or are we part of a much larger system at play

that perpetuates the creation of the savior complex in education as a tool of

colonization? What if the profession of schooling is one of preparing the next

generation for mental and other forms of slavery?

The history of

savior complex has much deeper roots. Many missionary movements the world over,

have been based on the belief that it is the God-given duty of the “saved” one,

to “save the savages.” It also has deep historical roots in education.

The very first

boarding schools in the U.S., created for Indigenous, First Nations, so-called

Native American peoples, were run on the belief that these “savages needed to

be saved.” That history can best be found in the book “Kill the Indian, Save

the Man” by Ward Churchill. Quite honestly, many of our schools today trace a

lot of their practices to the ones from the boarding school. There are new

saviors and new savages today.

Zero tolerance

and no excuses schools are the grandchildren of the slave master (now the

headmaster or principal) boarding school. Colonization manifests itself in

bells ringing (like in prison), uniforms for conformity, lining kids up,

ordering every minute of their day, presenting them with a daily white lens of

history in almost every subject, teaching them only colonial languages, having

armed guard “police” the youth on campus, metal detectors, bars and fences in

many “hood” schools, and on, and on, mostly for “their own good,” oh and of

course manners, etiquette and preparation for JROTC and the army, can’t forget

that. This cements youth to know their place, knowing when to speak and how,

know how to behave, knowing what and how to think, knowing what proper language

to use, know what is proper, and it produces on average 3 million “pushouts”

every year nationwide, and millions of youth who are anesthetized, numbed, to

conquest. Conquest starts early and we punish Black and Brown (and most other

kids of color and poor kids) students very early on, starting in kindergarten

(or preschool and daycare sometimes) because they are so “unruly” (or hyper,

behavior issues, ADHD) that they must be constantly “suspended” to beat the

rebel out of them.

Schools value

multilingual education to a certain extent, but only if the languages are

European. I don’t need to remind you that English comes from England, and

Spanish comes from Spain. So, in most schools, we are OK with helping kids

reach their bilingual European self and that has a deep impact for Black and

Brown children whose indigenous languages have been robbed from them in school.

Kids do not speak Nahuatl, Swahili, Quechua, Mam or the language of revolution,

on the daily, by colonial design, even in most dual-language or multi-language

schools. Dr. Angela Valenzuela describes this practice as a form of

“subtractive schooling.” She theorizes that the more time that Brown children

spend in most US schools, the more that gets subtracted from them; their pride,

roots, culture, history, languages, sense of belonging, and their deep sense of

agency to stand up to this colonial state and rise up.

White sociologist

Dr. James Loewen wrote a book about it, that based on my experience working

with educators nationwide, hardly anyone has read, specially teachers. “Lies My

Teacher Told Me” is an anchoring text that has been de-facto banned from must

public schools. On the original cover of the book, Dr. Loewen placed a huge can

of white wash paint on top of US history. He was not pulling any punches, and

maybe we shouldn’t either if we’re really serious about being the educational

leaders that we aspire to be; however, ethnic studies is still at best, an elective

othering, a thing to bring in to the curriculum, but never central to US

history.

Savior’s complex

manifested itself in me in so many ways as an educator of “color.” I can only

imagine where it must live for white educators and leaders who have not “experienced

oppression” in the same way, and the “woke” ones, who funnel our kids to “fit

in” to what is, and not stand in solidarity with and for “what must be.”

One of the areas

where my savior’s complex lived in is in a deeply held belief in my students.

By the way, you

have to know that I have a good heart, and that I have amazing espoused values.

I guess I have to state that to deal with my own fragility as I want to only be

seen by my intent, but not impact, at least not yet. As you know, espoused values

are those amazing flowery words that we share with the world and even with

ourselves about what we supposedly stand for. I’ve heard them all; rebel

teacher, anti-racist educator, educational activist, freedom fighter, so on,

and so forth. However, my enacted values were not always aligned with what I

shared with the world, and even with myself.

I “love” my

students (espoused value). I saw myself in my students, and that was deeply

problematic for so many reasons. I oftentimes funneled everything that they were

going through, through my own experiences and lenses. I oftentimes made their

journeys about me. Their stories made me cry, both because I cared, but also

because they touched the pain and unresolved issues inside of me. That was

completely unfair to them, unprofessional, and I was just a very poor educator

who was neither trauma informed nor resiliency informed.

I used to have an

un-minted doctorate at noticing and pointing out the injustice in other

educators, even in this reflection, but not my own. I’m still a work in

progress here. You have every right to question both the writer and the writing

here, but I hope that after you throw out what is not useful, you still hold a

mirror up to yourself, to the system, and are able to critically reflect on more

than just the imperfect writer of this piece. In that spirit, I learned to

become hyper sensitive of deficit language that others were saying, but not my

own deeply ingrained deficit thinking that was even more problematic.

If I ever heard

an adult say the words “at-risk youth,” I would flip it and say well they’re

only “at risk of creating a revolution.” Isn’t that cute? I had catch-phrases

for everything. But deep down inside, when students were going through

difficult things, I only saw them through their pain points, their

intergenerational trauma, and not their intergenerational wisdom. I took their

struggles home with me and didn’t know how to carry them in an empowering way.

I kept wanting to tell myself that I meant well. That I mean well. I carried

their trauma and maybe assumed that it would break them, because all I heard

was the litany of labels thrown at them/us: “minority” (and not minoritized),

“free and reduced lunch,” “underprivileged,” “socio-economically disadvantaged,”

“far below basic,” “first generation,” “immigrant,” and though I learned to not

verbalize the label, I also never really saw that they were (cap)able (of

revolution).

One of the words

I hate the most is “pobrecito” (oh poor little one). That appears to be one of

the most patronizing and patriarchal words that creates a particular teacher

gaze where we see the difficulty that kids and communities are struggling with,

and then we feel sorry for them. Sympathy is what normally comes, empathy is what

some people aspire to, but solidarity looks very different, and I’m still not

100% sure of what that may look like as I take the luxury of sipping my $4 cup

of coffee, with my fancy laptop out, as I write what may appear to be a

self-serving, pompous pseudo self-reflection during the “work” day with the

“freedom” to “reflect,” or if I teach in the hood, but live in the ‘burbs.

I think that all

of the films that I have watched, all of the deficit articles that I have read,

my own subtractive schooling experiences from kindergarten to 12th grade, have

placed a deeply ingrained savior’s complex bug in the back of my brain, and it

is proving to be extremely difficult to unlearn it. I have also gained a deeply

held inferiority complex in the agency of our people to truly be free.

I don’t know that

I really believed in the agency of my students to truly change the world, or

that our barrios and communities could truly create revolution. I started to

believe in the power of the empire and it manifested itself in not allowing me

to dream of what true freedom could look like. I gave too much power to the

prison system, the schooling inculcation system, the multiple layers that

create poverty, as somehow much bigger and stronger than my faith in my

students and in our communities. See, I have been trained to always study the

wrong things, like reform, instead of revolution. So, I would go home and cry.

I felt so bad for what was happening. Students are getting arrested. Students

are getting deported. Students are losing their homes. Students have very

little to eat. Students are taught that they can’t fully change the world. I

began to see all of the world through this lens, and realized how ineffective I

had become.

The only tired

cliché solution that I could offer them is to prepare them for college. I would

say ridiculous things about how great it would be to get a higher paying job,

and none of this was about deeply believing that empowered communities could

truly change the world. I just saw my kids as 21st century worker bees who

should escape the barrio/hood narrative.

That’s why I am

now in savior’s complex and poverty porn rehab. I am currently not teaching

students anymore. I don’t deserve to. Honestly, I wish a lot of people would

leave the profession, at least long enough to self-reflect. I have a lot to

unlearn before I get the privilege to be with students again. I am now on a

listening campaign as I hear from hundreds of students throughout the country

who are telling me how deeply they have been scarred by school.

I must admit I’m

angry.

I must admit I’m

highly skeptical of educational reformers, including myself, so I’m done with

that label.

I must admit I

find corporate money in education highly suspect, and deeply problematic.

I find

“well-intentioned” people to be those “nice” slave masters and colonialists who

had house negroes be a part of their foundations, non-profits or schools.

I feel like a

house negro who went to Harvard, and a bunch of other colonial spaces, wearing

the suit just to get by.

I am shuckin’ and

jivin’, and getting quite tired of it.

I am trying to be

a school designer, but I find myself going up against everything that has

created the colonial plantation now called school, trying to tell us how to do

it, and under what terms.

If anyone out

there feels this way, might we unite?

If you are done

with this corporate, poverty porn, dog-and-pony non-profit industrial complex

show, will you holla’ at a brother?

Rehab members of

the world unite.

These are the

confessions of a miseducated educator blinded by savior complex and the poverty

porn within.

What’s your

truth?

What’s your

reflection?

How might we

“see” blind spots?

How might we

maintain colonialism and what would it mean/look like to stop?

One

clap, two clap, three clap, forty?

By clapping more or

less, you can signal to us which stories really stand out.

Educator. Activist.

Author. Co-Founder Homies Empowerment