Motion reopens 35-year-old case over educating students with limited English skills

Hearing in Austin on July 24 over quality of education for students with limited English abilities.

By Francisco Vara-Orta

AMERICAN-STATESMAN STAFF

Saturday, July 08, 2006

The complaint is decades old: Texas does not do enough to educate children with limited English skills.

It's been 35 years since a federal judge agreed with that claim and ordered the state to fix the problem. But in a court hearing this month in Austin, civil rights groups will argue that Texas is still failing miserably and will demand that students with limited English skills be placed in well-designed and adequately funded, staffed and monitored programs.

State statistics show that students with limited English are more likely to fail state achievement tests, and although the consequences for failure are high — students must pass to graduate from high school and to be promoted in some grades — the Texas Education Agency doesn't hold districts accountable for the performance of these students in the same ways it holds districts accountable when other student groups fail.

Dismal academic results have prompted the Mexican American Legal Defense and Educational Fund, and other civil advocacy groups to file a motion in February in the U.S. Eastern District Court in Tyler.

It's the continuation of a 1971 lawsuit in which the court first ruled that Texas must offer programs to get limited-English students up to other students' levels. MALDEF's argument is that Texas is failing to meet that goal.

After months of legal wrangling, senior U.S. District Judge William Wayne Justice ruled in May that the case can be heard in his Austin court on July 24.

State officials declined to comment on the legal points of the case, but Georgina Gonzalez, director of the state's Bilingual Education and English as a Second Language unit, said Texas is committed to helping limited-English students, who she says have shown marked improvement on the Texas Assessment of Knowledge and Skills test, after a few years in the system.

"There are many challenges facing the students who are trying to learn a new language and culture on top of learning the curriculum," Gonzalez said. "We can't give (them) any easier form of the TAKS test. Instead, we have to push them up to the same standards that we hold for other students."

Texas enrolled 711,737 students in the 2005-06 school year under the designation "limited English proficient," about one in six of the state's 4.5 million students.

The limited-English category includes elementary students who are taught through bilingual education, in which students learn mostly in their native languages, and middle and high school students in the English as a Second Language program, in which students are immersed in English and get limited help with coursework in their own language.

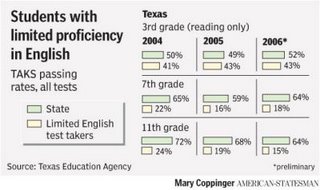

Students with limited English skills typically score below state averages on the TAKS, but the problem is particularly apparent with English as a Second Language students.

Just 18 percent of seventh-grade English as a Second Language students passed all parts of the TAKS, a rate that's 46 percentage points lower than the 2006 average for all students. Only 15 percent of 11th-grade English as a Second Language students passed all of the high school exit exam, compared with 64 percent of all students. Those results show a decline from 24 percent passing in 2004.

"It seems that the Texas take on the 'No Child Left Behind' motto doesn't include (limited-English) students," said David Hinojosa, MALDEF's lead attorney on the case. "The numbers speak for themselves and speak volumes."

Texas' accountability system is intended to ensure that all students are receiving an adequate education. Various categories of students — such as a particular ethnic group or gender — starting in third grade all must pass state achievement tests at certain levels, or schools and their districts can face sanctions.

Poorly performing schools and districts could receive low ratings, and campuses that don't improve could be forced, as Johnston High School was about two years ago, to restructure, allow students to transfer to other schools or eventually be taken over by the state.

Though the state collects performance information on students with limited English skills, it doesn't force districts to address poor passing rates among limited-English students on the TAKS as aggressively as it does for ethnic groups, for example.

If successful, MALDEF's motion would require on-site, in-person monitoring for districts where the TAKS passing rates among limited-English students are the lowest.

In addition, the motion requests that the state:

•Ensure that the passing rates of elementary and secondary students are considered separately.

•Investigate districts that, based on U.S. Census Bureau data, appear to underreport the number of limited-Englishstudents enrolled.

•Intervene in school districts where significant gaps exist in the achievement, promotion and dropout rates of limited-English and English-speaking students.

"Districts only get reviewed if (limited-English) students fall more than 10 percentage points below the state standard for that exam," Hinojosa said.

In 2004-05, 180 districts were flagged for review, but just two turned in corrective action plans required in such situations, Hinojosa said.

The state uses a system that primarily relies on computer analysis of test scores and district self-assessments to determine compliance with bilingual education laws. Under the system, poor performance at specific schools can be masked by the district's overall performance.

"That means for a district that relatively higher performance at one school on the TAKS can cancel out failing performance at another school, and students that need help aren't going to get any," Hinojosa said.

Limited-English students are four times less likely than students overall to pass the high school exit exam, according to state data.

Such students were more than twice as likely to be held back a grade; 14 percent weren't promoted in 2003-04 compared with 6.3 percent of students overall, and limited-English students dropped out at twice the rate of Texas students overall.

But state education officials said limited-English students show rapid improvement on the TAKS once in Texas schools.

In 11th grade, for example, 44 percent of students with one full year of limited-English instruction passed, compared with 15 percent of their "newcomer" colleagues.

Hinojosa said no matter which way the numbers are presented, they show a problem that needs to be fixed.

"The TEA keeps telling us to look at this or that breakdown, but ultimately, students are held to the TAKS test scores, and that holds them back or leads them to dropping out," Hinojosa said.

MALDEF timed the filing of its motion to coincide with the State Board of Education's debate about encouraging state legislators to allow elementary schools to choose English as a Second Language courses instead of the bilingual curricula now required.

The board, which has no legal power to change the law, has not decided on a recommendation.

"I don't think there is solid evidence that bilingual education works," said Education Commissioner Dan Montgomery, whose district includes Austin. "But I'm not for English-only either. I'm not advocating a sink or swim policy. More research is needed."

Montgomery said he thinks state law should be changed so that schools may use English as a Second Language or other English-immersion programs approved by the Texas Education Agency to cut the costs of bilingual education. In the 2004-05 school year, the state gave districts $965.3 million for bilingual education and ESL programs.

The push for English-only immersion, Hinojosa said, "is entirely irrelevant because the State of Texas has adopted a bilingual education code and recognizes that the best way to ensure educational opportunities is through bilingual programs for primary and (English as a Second Language) classes for secondary students."

Martha Garcia, the Austin school district's bilingual education and English as a Second Language program director, said, "There's a common misperception by outsiders that we don't teach English or we want to keep (limited-English) students only speaking their native language, but that's absolutely false. We believe that using the native language is crucial in introducing and fully developing their English."

Jill Kerper Mora, an associate professor at San Diego State University and a former bilingual education consultant with the state, said studies she conducted indicate that limited-English students who receive more instruction in their native languages learn English faster and perform better academically.

Districts have options in structuring their programs, typically using more English to teach math and science and native languages to teach reading in the primary grades. Secondary students get a heavier dose of English in all areas.

"In middle school and high school, you get no native language support, only (English as a Second Language) instruction, and the teachers don't even have to know Spanish or other languages," Mora said. "That paints a strong picture of maybe what would be a more effective method at the secondary level."

fvara-orta@statesman.com; 445-3616

Find this article at:

http://www.statesman.com/news/content/news/stories/local/07/8bilingual.html

No comments:

Post a Comment