Fascinating read on how it came to be that a food so nutritious to Mesoamerican peoples could be so dangerous that it was outlawed, especially since it helped form the "near-perfect core" of their diet. I think that all of the reasons provided below are mutually consistent in explaining why it was banned, particularly considering the end-goal of weakening native peoples so that they could be conquered and colonized.

If you've not tasted it, it's delicious. You find it in some cereals in some stores. I like it in my smoothies. I've eaten it in mole in Mexico, too. I was not aware of any of these aspects of its history, however, that I indeed find intriguing.

-Angela Valenzuela

Foods of the Americas: Amaranth, the Outlaw Grain

By Chola con Chelo | Nov. 18, 2017

Huaútli is the Aztec name for a plant so important to the people, it was banned by the invading Spanish Empire led by Hernán Cortez and the Catholic Church in 1519.

Today huaútli is most commonly known as amaranth, a super-food gaining worldwide recognition as a high-protein plant edible that could easily figure into the solution for world hunger. Although not considered a grain, the tiny amaranth seeds contain eight to nine grams of protein in a one cup serving, offering a nutritionally complete plant food that has all the essential amino acids needed by the human body, without gluten.

Today huaútli is most commonly known as amaranth, a super-food gaining worldwide recognition as a high-protein plant edible that could easily figure into the solution for world hunger. Although not considered a grain, the tiny amaranth seeds contain eight to nine grams of protein in a one cup serving, offering a nutritionally complete plant food that has all the essential amino acids needed by the human body, without gluten.Together with corn, beans and chia, amaranth was a key part of the near-perfect core diet of Mesoamerican Indian civilizations, and a tribute item demanded by the Aztecs. But the invading conquerors prohibited its cultivation and consumption calling it an ungodly pagan food, something full of sin. So for hundreds of years under the rule of Spain, amaranth all but disappeared from the face of the earth except in the highlands of Oaxaca and to the south among the Mayan people where its cultivation most probably began some 10,000 years ago.

But more importantly, it was used in religious rituals offered to certain deities, as a dish called tzoali, a delicacy of popped amaranth and sweet magüey blue agave syrup or honey, mixed together and shaped. Today those same tzoali are called alegrías and can be found in bakeries and stores throughout Mexico and in the Southwestern United States, or anywhere Mexican culture and cuisine flourish.

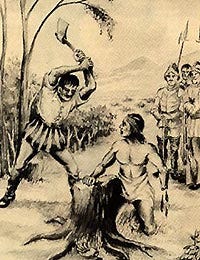

Yet when Spain invaded the Americas, they soon criminalized the cultivation of amaranth, as they did with the quinoa plant in South America. In doing so they banned the cultivation of one the world’s best sources of plant protein. The Spanish Empire imposed the most cruel and uncompromising punishments for growing huaútli, including cutting off the hands of those who dared to plant it.

So why did this beautiful nutritious and mystical plant elicit such a savage response from the invaders? This atrocity was most likely triggered by the importance of amaranth both in the people’s diet and in their spiritual life, a plant rightly held in high esteem.

Upon their arrival, the Catholic priests were horrified to find that amaranth was considered a deity and used in religious ceremonial rituals. It was consumed and mixed, according to some sources, with the blood of people who were sacrificed, and was perhaps a tad too close to the religious ceremonial ritual of the holy Eucharist, the Catholic ritual that consecrates the body and blood of Christ and is also eaten. But the Eucharist is of course not considered savagery by the church. To the contrary, it is considered a blessed sacrament.

As many scholars have noted, amaranth was an important part of the diet of warriors as well as a sacred plant that came into the cross-hairs of the Church’s war against paganism. So the more likely truth is that the criminalization of amaranth was both a military strategy intended to weaken the Aztec people allowing for an easier conquest. It was also a brutal tactic used by Catholic Church to eliminate any practices or evidence of an indigenous religion.

Like all warriors, the Mexica Eagle Guild Warriors ate amaranth and were responsible for fighting off and killing about 80% of the Spanish invaders who died in battle, despite their iron swords and their use of horses and dogs as weapons of war. So it was urgent for the Empire and the Church to weaken and crush the masses of people and their warriors by any

means necessary.

Despite its near extinction, today’s amaranth, the hardy survivor huaútli, can be found in contemporary cooking from granola to pancakes and is once again taking it’s place as an important plant food in defiance of its illicit past.

Diverse varieties of amaranth were cultivated all the way to the lands of the Inca people in the South American Andes, where it is consumed to this day. High in protein and the essential amino acid, lysine, amaranth found its way to Europe and is even consumed in India where it is known as rajeera, or the king’s grain.

How ironic that this offering of forbidden toasted amaranth seeds, held together by the sweetness of agave nectar and honey, made round in the shape of the sun and the circle of life, should survive to be called alegría, happiness or joy. No blood this time. Plenty of that was spilled by the Spanish invaders.

From Mesoamerica to East of The L.A. River, from street vendors to neighborhood mercados, bakeries and marketas you will find amaranth sold as the popular treat called alegría, the Spanish word for happiness or joy.

WRITTEN BY María Elena Gaitán (Chola Con Cello) writes about her obsessions, musings and rants from the heart of the universe, East of the Los Angeles River. This is first in a series about the global contribution, politics and cultural impact of Pre-Columbian foods. Thank you for following.

No comments:

Post a Comment