Yes, Asian Americans are omitted from U.S. History books, not unlike most other groups, including women. Read this post, to learn of the recent struggle for inclusion of Asian American Studies, as well as Mexican American, African American, and Native American Studies before the Texas State Board of Education.

"Erasure" is not quite the word for this as it suggests something was present and then removed. Still, getting erased in historical memory through acts of omission is terrible. So are distortions and errors of interpretation when they occur. This arguably disrespectful posture toward Asian Americans will get further aggravated by House Bill 3979 that goes into effect this fall. Among other things, it prohibits the teaching of current, controversial events like say, the Atlanta shootings that targeted Asian women last spring.

A first-year teacher cited herein, adds another layer of difficulty, namely, the role of standardized, high-stakes testing as itself an agent of curricular whitewashing and teacher control. To many of us in the fair and valid assessment movement, this has been obvious for such a very long time. Complicating all of this further are State Board of Education politics.

“If the state of Texas doesn't say, this is important material for you to learn, it's hard for us to fit it into the curriculum,” Gross said.

The seeming impediment of the wide diversity of the Asian American student population suggested within should not be viewed as a problem, in my view, especially when the political representation of Asian American policymakers, lawmakers, and teachers structure out their voices to begin with.

Short of what our imminent Asian American Studies elective course will offer—once TEKS standards for it are established—my main take away from this important statement on Asian American history is that Texas state curricula reflects the interests of those in power. And those in power are either ignorant or willfully blind to Asian Americans' historical experiences primarily because it might empower this growing demographic. So unfortunate.

This is such a small, shameful, defensive posture that forfeits important historical knowledge that could deeply enrich our intellects and social relations in an increasingly interconnected world.

-Angela Valenzuela

‘Erased From The History Books’: Why Asian American History Is Missing In Texas Schools

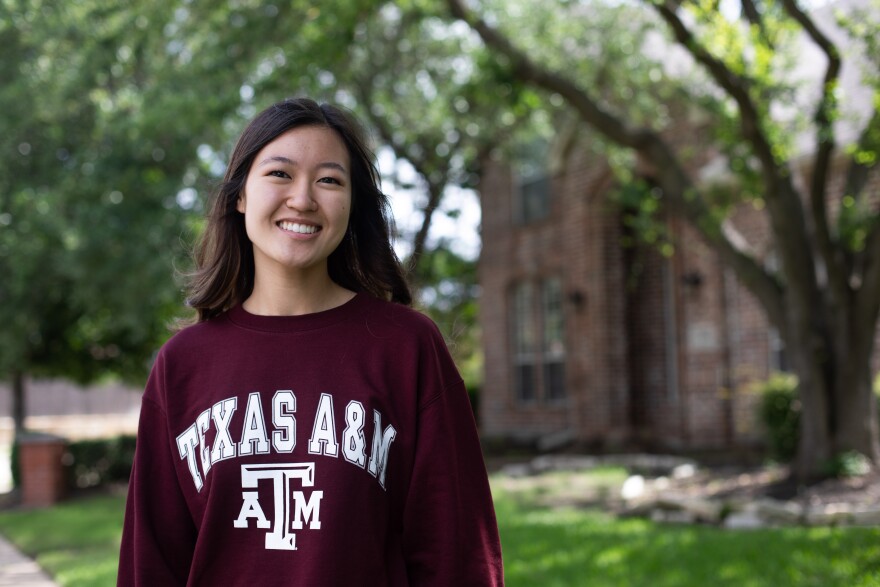

When Anita Chaiprasert looks back on what she’s learned in school, she only

remembers a handful of times when Asian American history was mentioned.

Chaiprasert said she vaguely recalled being taught about the Vietnam War. The

Plano West High School senior couldn’t remember a single Asian American

historical figure. As a Thai-American, Chaiprasert said she didn’t feel represented in

lessons or textbooks.

“It’s not really talked about in school,” said Chaiprasert.

She spoke to KERA a few weeks before graduation and is headed to Texas A&M

to study biology as a pre-med student in the fall. Chaiprasert spent all of her school

years in Plano ISD classrooms, but her experience is not unique. Students and

teachers across Texas shared similar stories with KERA.

“Whenever you get to United States history, Asian Americans tend to get erased from

the history books,” said William Gross, a high school U.S. and world history

teacher in Austin.

From educators to textbook advisors, experts say state standards, teaching

approaches, textbooks and politics all contribute to the erasure of Asian

American experiences when history is taught in Texas schools.

'It’s Often Left Out Or It's Just An Afterthought'

There’s simply not enough Asian American history taught in schools, says

Sarah Soonling Heng Blackburn, a teacher educator with the Southern Poverty

Law Center’s Learning For Justice program.

“It’s often left out or it's just an afterthought,” she said. “Maybe kids will get a

couple of sentences about Chinese railroad workers. Then they'll get a couple

sentences about Japanese internment. That's typically about it.”

She said students don’t learn about key figures like Yuri Kochiyama or

Fred Korematsu, and how they worked in solidarity alongside other communities

for civil rights.

Asian Americans are largely overlooked in immigration narratives, according

to University of Texas historian Madeline Y. Hsu. She launched a website to

help educate high school students on immigration policy.

“We need to understand Asian American history, because it actually pertains

to the United States broadly as a nation of immigrants,” she said.

There’s no expectation that Texas students graduate with an understanding

of the rich diversity and complexity of Asian American experiences.

“It's not a deeper conversation about the longevity of Asian American history,

for example, the contributions of Asian Americans, their struggles, their

intersectional struggles with other groups, like Latinx and Black Americans,”

said Mohit Mehta, a University of Texas PhD student and former Austin

elementary school teacher.

Mehta said Texas public schools need to go deeper than what he calls the

“Three F’s”: food, fashion and festivals.

'If The State Of Texas Doesn't Say This Is Important Material...'

Public education in Texas is shaped by the Texas Essential Knowledge

and Skills standards, the TEKS. The standards are set by the State Board

of Education, a group of elected members responsible for changing

curriculum standards and adopting textbooks. State exams — the State of

Texas Assessments of Academic Readiness (STAAR) — are based on the

standards.

As a first-year teacher, Gross has a fresh perspective on how the TEKS shape

what students learn. Educators face pressure to teach to state tests.

“If the state of Texas doesn't say, this is important material for you to learn,

it's hard for us to fit it into the curriculum,” Gross said.

When it comes to Asian American history, Gross says the state standards

outline just two major topics: the Chinese Exclusion Act and Japanese

internment. He said the curriculum standards don’t include any named

Asian American historical figures.

A nationwide conversation about the erasure of Asian American experiences

in school curricula has surged amid rising anti-Asian discrimination and

violence, including the Atlanta shootings in March when a man targeted

women of Asian descent killing eight people.

In recent years, the State Board of Education (SBOE) has made steps

towards more diverse course standards for social studies. In 2018, the

elected board approved a Mexican American studies class. Last year,

they approved an African American studies class. Over the past two years,

the SBOE has listed Asian Americans as one of the groups that could be

included in the state’s ethnic studies courses, but an official state-accredited

class on Asian American history has not been established.

statewide high school elective arrive for a 2014 Texas Board of Education

hearing in Austin.

Texas State University history professor Frank de la Teja says the process of

reviewing standards is expensive, time-consuming and politically fraught.

The TEKS were established in 1997. De la Teja is a former state historian for

Texas who helped review the state’s social studies standards that were adopted

in 2010. He said ideally the social studies standards ought to be reviewed every

four or five years, but the most recent review was in 2018.

“The problem is that the longer you go between reviews and revisions, the more

that events wind up being left behind,” he said.

Textbooks: Another Important Part Of The Equation

KERA borrowed a teacher's edition of a state-approved McGraw Hill "United

States History Since 1877" textbook from a Dallas ISD high school teacher.

The book is 834 pages and weighs more than 7 pounds. Its index lists just

one page that references the term "Asian Americans.”

Two sentences on that page talk about Asian Americans’ service in the U.S.

military during World War I: “Some Asian immigrants fought on the side of the

United States even before they were citizens. Though they faced discrimination,

many Asians served in the U.S. Army with distinction, being granted citizenship

in recognition of their contributions.”

The Texas Education Agency, which oversees public education, declined to

comment to KERA on the record about curriculum or textbook standards for

Asian American history.

De la Teja said creating a textbook has become a precarious process of

balancing political and economic concerns. Publishers must appeal to different

groups including parents, teachers, publishers, boards of education and state

boards. Appealing to all these groups often means preserving the status quo.

The history professor advised Houghton Mifflin on textbooks for middle and

high school history classes said changing what’s in textbooks is an

“evolutionary” process because publishers proceed cautiously.

“What that means is that history inches forward in terms of our understanding

of what should be included, what should be stressed, what new events or

what more recent events should be given a considerable amount of attention,”

de la Teja said.

Another complicating factor, de la Teja said, is that “Asian American”

describes so many diverse populations. Americans of Chinese or Japanese

descent are commonly referenced in textbooks. But de la Teja said textbooks

haven’t “caught up” with recent Texas history, which includes the immigration

of many South Asians and South East Asians.

Textbook advisers like de la Teja are expected to present convincing arguments

for changes, but it’s ultimately up to the State Board of Education to accept

or reject expert input.

Given that the standards don’t prioritize the teaching of Asian American

history, de la Teja said “it's going to be up to teachers to address those

issues that matter to the students in front of them that go beyond the facts

that are laid out in the textbooks.”

Straying From The TEKS Script To Give Students A Fuller Picture

That’s exactly what teacher William Gross has tried to do in his classroom.

The high school teacher uses what he calls a “TEKS-and” method, using the

standards as a jumping off point to provide a little more historical context.

“According to the TEKS, the Chinese Exclusion Act was all about jobs,” he said.

“But with that, you can also stray away and talk about the lynchings that

were happening of Chinese Americans and Asian Americans all up and down

California.”

So in addition to lessons about the Chinese Exclusion Act and employment,

which every Texas student is required to receive, Gross’ students also

learned about how the hostility towards Chinese immigrants helped fuel

racist violence.

U.S. National Archives

A photo of Lee Wai Shee and her children taken in Honolulu by the

Department of Labor Bureau of Immigration, sometime between

1913-1933.

While the standards provide certain guidelines, they leave room for

interpretation — which is up to the discretion of individual teachers like Gross.

That means educators must consider a variety of factors: time constraints,

their knowledge and confidence on a subject, their willingness to go

beyond the standards and the limitations set by their school, district and/or

region. But that calculation often weighs heavily against deviating from the

standards, especially in a school year upended by the pandemic and the

Gross said using his “TEKS-and” method has been the way he’s tried to

affirm his students in the classroom and feed their hunger for knowledge.

After the Atlanta shootings, Gross was peppered with questions from students

who were trying to piece the history together.

“It's kind of like trying to read a chapter book where every other chapter is

taken out. You get bits and pieces,” he said. “You’re kind of confused,

like what's happening and why did this happen?”

By omitting certain stories and figures, Gross said it was hard for students

to understand the context of Asian American discrimination in the U.S.

'We Have A Political Process'

Ultimately, politics is central to how Asian American history is taught in

Texas schools.

New legislation would make it more challenging for Gross to provide that

context. The Senate has passed bills SB 2202 and HB 3979 that would

restrict the discussion of race, current events and public policy in the

classroom. HB 3979 has already been signed by Gov. Abbott.

When discussing the bills, proponents have equated this idea to critical

race theory (CRT): An intellectual movement born out of law schools that

teaches that racism is embedded in systems and structures in the U.S.—

such as legal institutions — rather than just being the product of individual

prejudice. CRT is typically taught in colleges and universities.

The bills will limit how public school teachers talk about race in the classroom,

making it harder for them to address current events like the Atlanta shootings

or rise in anti-Asian hate crimes during the pandemic.

Gross said the bills would restrict what he could say when teaching important

Asian American historical topics.

“They don't want teachers to talk about race,” he said. “So if we're talking about

the Chinese Exclusion Act, we can't bring up the topic of race. If we're talking

about Japanese internment camps, we can't talk about race.”

But the critical race theory bills are only the latest aspect of the political

controversy around what students are taught in Texas. Some of the politics

is inherent to the partisan, elected nature of the State Board of Education.

“We have a political process,” said de la Teja. “It isn’t just educators who

determine what the standards are. We have elected officials who do that

and there’s always horse trading in politics.”

The 15-member board now seats nine Republicans and six Democrats.

The standard-setting board is a frequent battleground for social and cultural

issues. In the past, the board has received widespread attention for debates

during its board meetings, including a proposed Mexican American studies

textbook that was deemed racist and its abstinence-first approach to sex

education.

KERA reached out to several board members for this story, but they didn’t

respond to requests for comment.

De la Teja said it’s often up to constituents to advocate for changes they’d like

to see — the more people that speak up, the more likely it is that elected

members will respond.

“If they make their interests and their needs felt by their elected members to

the State Education Board, then the State Education Board members from

representing those areas are going to be asking questions that they wouldn't

ask if nobody's talking to them about it,” de la Teja said.

Constituents like 19-year-old Catalina Chang, a sophomore at the University of

Texas at Dallas, are advocating for changes that will require public schools to

include more Asian American history. From elementary to high school, she

attended Fort Bend ISD schools near Houston. She remembers learning

about Japanese internment camps, Chinese railroad workers, the Chinese

Exclusion Act — and little else.

On April 29, she sent a letter to Matt Richardson, her local State Board of

Education representative. She urged him to incorporate more Asian American

history into K-12 curriculum.

“The lack of support and origin of these hate crimes stem from the erasure

of Asian American history in education. I urge you to recognize that ignoring

our past invalidates the struggles that AAPI [people] experience, which feeds

into the oppression and marginalization of Asians that our education denies,”

Chang wrote.

Half Taiwanese and half Korean, she said videos and infographics on Instagram

have supplemented the education she didn’t get in the classroom.

“I wish that I had learned more about the depth of Yellow Peril in school,”

she said, referring to the centuries-old xenophobic fear of East Asia in the West.

“I feel like now social media has increased our knowledge and our understanding

of where we come from.”

Acknowledging The Contributions Of All Americans

Some parts of the country are gaining traction in changing their social

studies curriculum after the Atlanta shootings. In May, the Illinois Senate

passed legislation called the Teaching Equitable Asian American Community

History Act that would require Asian American history to be taught in public

schools. If signed into law, Illinois would be the first state to adopt those

requirements.

Mohit Mehta

Mohit Mehta reads a book to a classroom of elementary students in Austin.

In Texas, a fast tracked standards review

presents an opportunity for change. Last year,

students launched a petition calling

for anti-racist curriculum, and pushed the

State Board of Education to accelerate its

social studies curriculum review. Originally scheduled for 2023, the review

of social studies TEKS has been pushed up to the 2021-2022 school year.

Still, educators, learning advocates and experts agree that the lack of Asian

American history in schools is a complex issue that will need to go beyond

changing standards and textbooks.

“It's not one thing that, hey as long as we have Asian American Studies

curriculum, that's going to solve all their problems,” Mehta said.

The educator said schools must also focus on improving training for teachers

and recruiting Asian American teachers who better reflect diverse student

populations.

It’s also about the mentality leaders have in addressing these issues, Mehta

said. Instead of justifying the need for more Asian American history because

of the growing population, it’s about acknowledging the humanity and diversity

of all students.

“It should be because we envision a world in which defining American doesn't

look one certain way, in which we acknowledge the contributions of all people

in building this society,” he said.

In Texas, the standards, textbooks, teaching and politics have created an

atmosphere where Asian American history is mostly absent. While discussions

about inclusive standards and skirmishes over legislation persist, Texas

students continue to miss out on Asian American history in the classroom.

Keren Carrión

Anita Chaiprasert holding a family photo. She says her Asian American culture

was never represented in her high school education.

Like Chaiprasert, who’s left thinking about how her school experience could’ve

been different.

“I wish I learned more about Asian [American] history,” she said, adding that

there’s European history classes, so why not Asian American history classes?

“Maybe it's because we're in America,” she wondered aloud.

Reflecting on her experience in Texas public schools, Chang said the

opportunity to learn more about Asian American history would positively

impact her community, maybe even the country at large.

“I do feel like what we're taught in school, especially at a young age, where

our minds are kind of molded. Essentially, that does trickle into the perception

of many Asian Americans in the United States today.”

Former KERA Intern Sriya Reddy contributed to this report.

No comments:

Post a Comment